The Secrets of City Life

Featuring a guided listen on city life and an interview with Görkem Akgöz

Three Podcasts to Understand … The Secrets of City Life

Starting in the mid-18th century, mass migrations and industrialization made “the city” a key character in the story of modernization. Cities became physical manifestations of our fear of and fascination with technology. Look at George Grosz’s Metropolis—a touchstone for sociologists and psychologists trying to understand the youth and adventure of cities and their impact on “human nature.” Today, 57% of the world lives in cities (a far cry from the less than 5% in 1750). What impact do cities and the technologies that shape them have on our lives? Read on to discover three NBN podcasts that explore what makes a city.

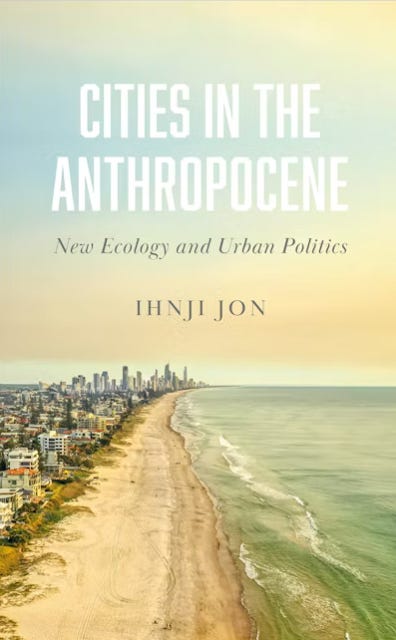

Cities in the Anthropocene: New Ecology and Urban Politics

One the most pressing and intractable issues facing city planners, politicians, and civilians is how to make their cities greener, sustainable and more livable. Ihnji Jon approaches this question with case studies of four cities: Tulsa, Oklahoma; Darwin, Australia; Cleveland, Ohio; and Cape Town, South Africa, arguing that a change in rhetoric could help to make urban environmental action more effective. Jon proposes changes that are directly tied to popular causes like riverside parks or low-impact development. This way, action can occur with support from people that might not be devoted to environmental causes. Jon describes this as the “neutrality of material things,” noting that projects need not be explicitly connected with environmental policy. Especially in cities like Tulsa and Darwin, where much of the population is connected to the fossil fuel industry, this approach helps drive progress despite political resistance.

Emerging Global Cities: Origin, Structure, and Significance

While most cities possess only a limited regional influence, some “global cities”—like New York, London, and Tokyo—have an impact throughout the world thanks to their commercial and cultural weight. Alejandro Portes and Ariel C. Armony look at the dynamics of “emerging global cities,” like Singapore, Miami, and Dubai. Despite different histories, these three cities have many similarities.

All three have placed a high premium on attracting young professionals, entrepreneurs, and capital. This has turned them into significant banking and financial centers—a key factor in gaining wider influence. These cities also share an intense focus on becoming global cities, spearheaded by what Portes and Armony call a “charismatic leader with an iron will.” They have invested resources into cultural and symbolic branding like Dubai’s construction of the Burj Khalifa or FC Miami’s acquisition of Lionel Messi.

In their quest to go global, these cities have also been the subject of criticism for environmental and democratic shortfalls. Portes and Armony’s study does an excellent job illustrating the complexity and challenges that come with trying to transform and reshape a major city.

Urban Surfaces, Graffiti, and the Right to the City

Sabina Andron examines how city surfaces— covered in graffiti, political posters, ads, notices, and more— leave their imprint on the values of a city. Urban Surfaces, Graffiti, and the Right to the City explains how graffiti became associated with criminality by many inhabitants and city officials. Andron asks prescient questions about what can be defined as art and how the physical space of a city concretely illustrates the changing landscape of its people, cultures, and values. She proposes understanding city surfaces—essentially anything that is publicly accessible or visible—as a commons that counterbalances, or works against, the securitization and privatization of cities. The book ends with a call for the “right to the surface,” a manifesto that spans political, aesthetic, and moral considerations in highlighting city surfaces as a collective space.

If you have listened to, and enjoyed, these three episodes, don’t stop here. NBN has many more episodes on the design, politics, and history of cities, from an account of how green spaces became a moral good to individuals that have shaped urban design, and much more.

Marshall Poe on Vietnam War Films

Make sure to subscribe to Pages and Frames, an excellent film blog for book lovers.

Scholarly Sources

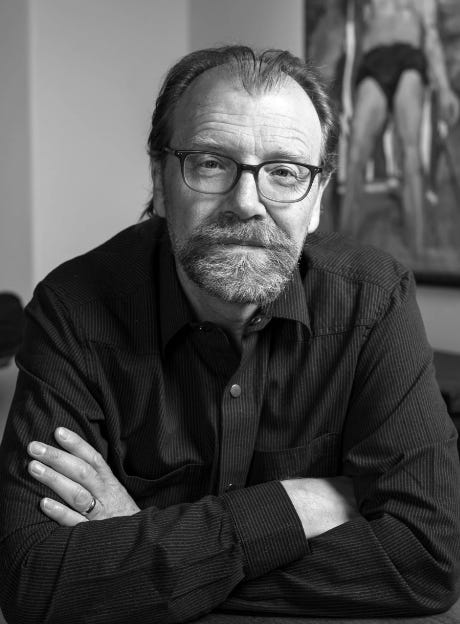

Görkem Akgöz, PhD is a post-doc researcher at re:work (IGK Work and Human Life Cycle in Global History) of Humboldt University and a lecturer at Orientalisches Seminar at Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg. She recently published In the Shadow of War and Empire: Industrialisation, Nation-Building, and Working-Class Politics in Turkey.

Q: What are you reading right now?

A: I'm juggling a few books right now, and I'd love to share a bit about two of them. Recently, during a visit to Vienna for a talk, I explored some Viennese literature. Among the gems, I picked up Stefan Zweig’s memoir, The World of Yesterday. I had read much of Zweig's work in my youth, but not this memoir. At first, I wasn't sure about it— Zweig's nostalgia for a bygone "lost world" felt kind of elitist and macho. But after about 50 pages, I was hooked. Zweig paints a vivid picture of himself and his world as the Habsburg Empire crumbles. His memoir, regardless of how familiar you are with the historical context, is crucial for a deeper understanding of that era. And, on a related note, I highly recommend The Radetzky March by Joseph Roth— an incredible historical novel about the decline of the Habsburg Empire that I also discovered while in Vienna. Reading Roth followed by Zweig provided a wonderfully complementary experience, offering both a fictional and personal perspective on the same transformative period in European history.

I have a passion for discovering books from diverse national literatures while traveling. Last month, while in Amsterdam, I had a delightful conversation with a bookstore employee who recommended Arthur Japin’s The Two Hearts of Kwasi Boachi. This captivating novel draws on extraordinary real-life events and tells the story of Kwasi, an African prince from the Ashanti tribe in the Gold Coast of West Africa (now Ghana), who, along with his brother Kwame, was given to King Willem I of the Netherlands in 1837 as surety in a deal involving illegal slave trading. Japin skillfully shapes the narrative as a memoir supposedly penned by Kwasi in his twilight years, residing on a tea plantation in Java at the turn of the 20th century. It's this powerful story of Kwasi as this figure caught between two continents, remembering these royal courts and dealing with identity, memory, and the enduring consequences of displacement inflicted by European colonialism.

Q: What is your favorite book or essay to assign to give to people and why?

A: When I teach sociology, I often start with C. Wright Mills' The Sociological Imagination. It's a cornerstone because it connects social sciences with history, something that's close to my heart. What really strikes me is how Mills anchors his ideas in the present—constantly reminding us of "today, in our present day." To underscore the temporal context, I would often challenge my students to guess the year of publication after reading these passages, and it is eye-opening. Most students don't initially pay attention to the publication year. But, like all authors, Mills was influenced by the circumstances of his era. He was a cultural critic of his time, fiercely critiquing American society and dissecting its norms and institutions. His work demands to be understood within the specific historical and social milieu of his era, a crucial lesson for students navigating academic texts shaped by their historical moment and responses to contemporary debates. Another compelling aspect of Mills' writing that resonated with my teaching was his passionate and often confrontational tone. He didn't shy away from expressing his frustrations, using his emotions to drive insightful critiques. I encourage my students to imagine the feelings of the authors we study, humanizing academic texts and connecting them to real-life experiences that inspired them. This approach bridges the gap between theory and history and, as Mills described, the connection between the social and the biographical, making complex ideas more relatable and impactful.

Q: Is there a book you read as a student that had a particularly profound impact on your trajectory as a scholar?

A: There are countless books that have left their mark on me, but I'll highlight one encounter that profoundly influenced my writing, both theoretically and narratively. Back in the mid-2000s, during my graduate studies at the State University of New York at Binghamton, I found myself drawn to a quaint second-hand bookstore. During one of my visits, I came across a well-worn copy of a hefty book adorned with an 1814 illustration: a man dressed in remarkably clean white clothes walking alongside a steam locomotive on rails. This image, titled "The Collier," depicted a coal miner from Middleton Colliery in south Leeds, returning from work in his distinctive workwear, and notably, it marked the first known print image of a steam locomotive. The contrast between the simple image of a laborer with his stick and the backdrop of a smoke-belching steam engine resonated deeply with me. This visual narrative, paired with the intriguing title The Making of the English Working-Class, vividly conveyed a world in perpetual motion. Looking back, I realized these visuals encapsulated the essence of the ideas and arguments found within the book's covers. What remains clear from that initial encounter is the sheer delight of flipping through random pages of the book, experiencing Thompson’s almost novelistic empathy for his subject. His intellectual and emotional impact resonated deeply, particularly his argument that "class" isn’t merely a structure or category but a dynamic force within human relationships. I was immediately captivated; it felt like a gradual infusion of thought-provoking insights coursing through my mind.

Q: Which deceased writer would you most like to meet and why?

A: My choice would undoubtedly be Yaşar Kemal, one of Turkey's most revered literary figures. I first encountered his novel İnce Memed (1955), later translated into English as Memed, My Hawk (1961), when I was just 12 years old. Over the years, I returned to his works, always filled with happiness at being able to read such a talented writer in my mother tongue. Like numerous writers in Turkey, Kemal faced personal consequences for his lifelong dedication to social justice and his outspoken affirmation of his Kurdish identity. To sit down with him at a rakı sofrası, our national tradition of long conversations over local liqueur and mezes, would have been a dream come true.

Q: What's the best book you've read in the past year?

A: It's been a bit more than a year, but I would still choose East West Street by international lawyer Philippe Sands. The book begins with Sands receiving an invitation to deliver a lecture in the Ukrainian city of Lviv. This invitation sparks a journey into his family's hidden past, leading to an astonishing series of coincidences that take him halfway across the world and back to the origins of international law at the Nuremberg trials. The result is a masterful blend of compelling family memoir and the story of the Jewish legal minds who laid the groundwork for human rights law at Nuremberg. The book is both profoundly personal and a meticulously crafted historical detective story. I vividly remember reading it while working on my own book and having a moment of self-doubt. I mean, how could I keep going if I couldn't match this level of writing? Luckily, that feeling didn't stick around for long.

Q: Have you seen any films, documentaries, or museum exhibitions that left an impression on you recently?

A: Last year, I had a fascinating experience in the museum world at the Museum der Arbeit (Museum of Work) in Hamburg. Despite my initial hesitation, given that my expertise lies outside museum studies, I accepted an invitation to speak at a conference on global work in museums. It turned out to be a wonderful opportunity to engage with museum professionals and discuss some of the pressing historiographical issues that we, as academic historians, grapple with. The experience prompted me to critically reflect on how challenging it is to translate theoretical insights from academic research into practical museum exhibitions. It has also inspired me to consider writing about global labor history and museums, exploring the intersection with public history more broadly. Moreover, my time at the conference also shed light on the precariousness of museum labor, a significant issue that resonates deeply within academia as well.

Q: What do you plan on reading next?

A: I’m excited to dive into Nino Haratischwili’s The Eighth Life (for Brilka), an award-winning family saga from Georgia. Much like East West Street, this book dives deep into a family's history, weaving together personal stories with the sweeping backdrop of 20th-century history, but it covers a much larger terrain. The story spans six generations over the course of a century—the "red century," as the narrator, Niza, describes it. From Tbilisi to Moscow, and on to London and Berlin, it promises to be a gripping journey through time and place.

I'm also looking forward to revisiting George Saunders’s A Swim in a Pond in the Rain. I tore through it last summer and loved every bit of it. Saunders calls it a "workbook-like book," a collection of essays drawn from his twenty years teaching creative writing at Syracuse University. Each essay pairs up with a classic short story by Chekhov, Turgenev, Tolstoy, or Gogol, showing us how great writing ticks and how our minds tick when we read. It's deepened my love for the craft of writing and kept me laughing with its sharp humor and wit.

Q: Who should read In the Shadow of War and Empire and why?

A: Anybody interested in labor, gender, state formation, citizenship, and ideology will find something of value in In the Shadow of War and Empire. I'm delighted by the book's reception across various academic disciplines—from labor and business history to political economy and urban studies. For enthusiasts of Istanbul's rich history, the book offers a captivating exploration of how industrialization profoundly shaped the city's development over a century. Think of it as a century-long stroll through Istanbul's industrial evolution, spanning from the 1840s to the 1950s. A significant aspect of the book is its micro-history approach, which immerses readers in the lives of factory workers within both the industrial complex and the bustling streets of Istanbul. This narrative style will especially captivate readers who appreciate biographical explorations in social history and the personal stories of individuals caught in the throes of historical change.

New Books, Links, and Other Things

Anne Applebaum, Autocracy, Inc.:The Dictators Who Want to Run the World (Penguin Random House, 2024)

Robyn Asleson, Brilliant Exiles: American Women in Paris, 1900–1939 (Yale UP, 2024)

Head spinning with all the recent news? Check out these Substacks for good commentary: