The Library of Mistakes

“Especially now, when the job market is frankly terrible and the universities are under siege, people need to go to graduate school with their eyes open, understanding it may not lead to a tenure track job.”

-Dr. Susan G. Pedersen

In this week’s newsletter:

Disorder with Jason Pack

Meet the Press: The Ohio University Press

Library of Mistakes with Russell Napier

Graduate Student Corner: Advice with Dr. Susan G. Pedersen

Disorder: The Podcast That Orders the Disorder

We are excited to share a fantastic podcast this week! Disorder: The Podcast that Orders the Disorder is hosted by Jason Pack (our new Podcasting Fellow) and co-hosted by Alexandra Hall Hall. Subscribe to their channel below, and read our Q&A with Jason and Alexandra.

Q: What's your show about?

A: Gone are the days of coherent international coordination. Rather than working together to solve pressing crises, many of the most powerful actors on earth are actively making those crises worse. Instead, with the rise of neo-populism, trade wars, inflation, anti-migration policies, and widespread popular fears over the delegation of sovereignty to the supranational level, major world leaders have sought to promote the “Enduring Disorder” and ride its whirlwind. Conventional geopolitical theory fails to explain this world in which many major states are no longer rationally pursuing their long-term interests. This podcast seeks to explain the real dynamics and interconnections that underlie our contemporary global system.

In Disorder, Jason Pack and Alexandra Hall Hall talk to people like Anne Applebaum, Jonathan Powell, Bill Browder, Miles Taylor, and Tom Malinowski, to learn from their experiences and to “Order the Disorder.” In the podcast, we cover topics like climate change, neo-populism, and unregulated cyberspace, analyzing how they feed into our era of disorder.

Q: Can you tell us about yourselves?

A: Jason is the inventor of the “Global Enduring Disorder” paradigm: the concept behind this podcast. He spent time in Lebanon and Egypt before moving to Syria as a Fulbright Scholar from 2004-2005. In 2008, he discontinued his first attempt at graduate work at Oxford, to move to Libya to assist Western businesses grapple with the late Qadhafi-era economic reforms. In Autumn 2010, he returned to Oxford and then Cambridge. As the Arab Spring reverberated around the Middle East, Jason drew upon his experience in Tripoli to advise Western policymakers and set up his own consulting company, Libya-Analysis LLC. In 2015, he founded a charity, Eye on ISIS, dedicated to promulgating accurate real-time information about the jihadi threat in Libya. In 2017-18, he returned to Washington, DC, to serve as the Executive Director of the U.S.-Libya Business Association. After resigning from this position, he wrote Libya and the Global Enduring Disorder and came up with his key ways of seeing the world.

Today, Jason is the Senior Analyst for Emerging Challenges at the NATO Defense College Foundation in Rome. He also leads a project entitled NATO and the Global Enduring Disorder, which produces a range of content attempting to sketch out a ‘unified field theory’ of our current era of geopolitics, while proposing actionable solutions to our most pressing collective action challenges. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Financial Times, The Guardian, and Foreign Policy, among others.

Alexandra Hall Hall is a former senior British diplomat, former British Ambassador to Georgia, and former Brexit spokesperson at the British embassy in Washington, until she resigned in December 2019 due to her concerns over the dishonest way in which Brexit was being implemented.

She is now a writer and commentator on British politics and foreign policy, including as a regular columnist for the Byline Times publication, and as a member of the Commission on Political Power, advocating for constitutional reform in the UK. She is a Trustee of the non-profit organizations Eurasia Foundation and Europe Foundation, Georgia, as well as a board member of the Brussels-based organization, Keeping Channels Open, which aims at sustaining dialogue and cooperation between the UK, the US and the EU.

Q: What motivated you to create this podcast?

A: JASON: Firstly, I feel that many of the world’s top table issues are interlinked, but are usually presented as if they were discrete. Issues about the Arab Spring are covered separately from issues about regulating AI. The climate change dossier and the tax evasion dossier are written about like they are not connected. But in reality these issues are all part and parcel of the coordination failures that underlie the Enduring Disorder. Secondly, I noticed that a lot of journalism, think tank reports, and other podcasts are really all about the problems. They diagnose them and tell funny stories about them. I wanted to create a show that was engaging and told real people’s stories, but also proposed solutions. That is why I made the Disorder Show and created our unique “Ordering the Disorder” segment.

ALEX: It’s helped me to learn a new skill set. It keeps me on my toes. It forces me to think through my biases and prejudices, be challenged by different viewpoints. I enjoy debating with Jason. It’s helped me find my voice in this mad, mad, mad, mad world.

Q: What have you learned from doing the show, so far?

A: ALEX: It has helped restore my confidence in mankind, to hear so many guests on the show, some of whom have been in the most difficult situations, retain hope, confidence, and determination to fight to make this a better world. The best recent example is Jason’s interview with Evgenia Kara Murza, the wife of Vladimir Kara-Murza, the Russian opposition politician serving a 25 year jail sentence on completely trumped up charges, for daring to criticize Putin. She was powerfully, righteously, angry - and hearing her made me want to fight her cause as well. The Americans on the show tend to be more confident and forward looking than the British. I don’t know if their confidence is justified, but they retain a faith in the power of America to do good in the world. Britain, post-Brexit, seems to be both in denial and in a complete funk.

Q: If you had to describe your show only using other podcasts, what would they be?

A: We aspire for the humor and unified focus of Remainiacs, the moral clarity of Sam Harris’s Making Sense, and the production value and editing of Doomsday Watch and Power Corrupts.

Q: If someone's new to your show which episode should they start with?

A: We are a narrative program based on the Enduring Disorder concept, so I think they should start all the way at the beginning with Episode 1 to get a hold on what we are about. Other episodes that really set the stage are: Ep3. The Rise of the Neo-Populists; Ep6. NATO: A Model for Ordering the Disorder?; and Ep11. The Psychology of Chaos.

Check out Disorder and listen to a recent episode, Neoliberalism: The Ulitmate Disorder? With George Monbiot!

In this episode, they chart the evolution of neoliberalism and how it has shifted core governance functions (like transport, health care, and security) from the public sector to private enterprises, leading to a new form of oligarchy. Plus: they look at the failures of centrist politicians to come up with compelling alternatives and they hypothesize about the psychological motivations of the wealthy elite. Finally, as they “Order the Disorder,” they put forward the need for a new political narrative that emphasizes community and solidarity - especially on a local level.

And subscribe to Jason’s Substack below:

Meet the Press: The Ohio University Press

The New Books Network is growing! We are excited to welcome a few new University Press Partners to the NBN. To celebrate these new partnerships we are highlighting one new press each week. Learn about our new UP partners and subscribe to their channels to stay up-to-date on the latest NBN interviews about the compelling books that they publish.

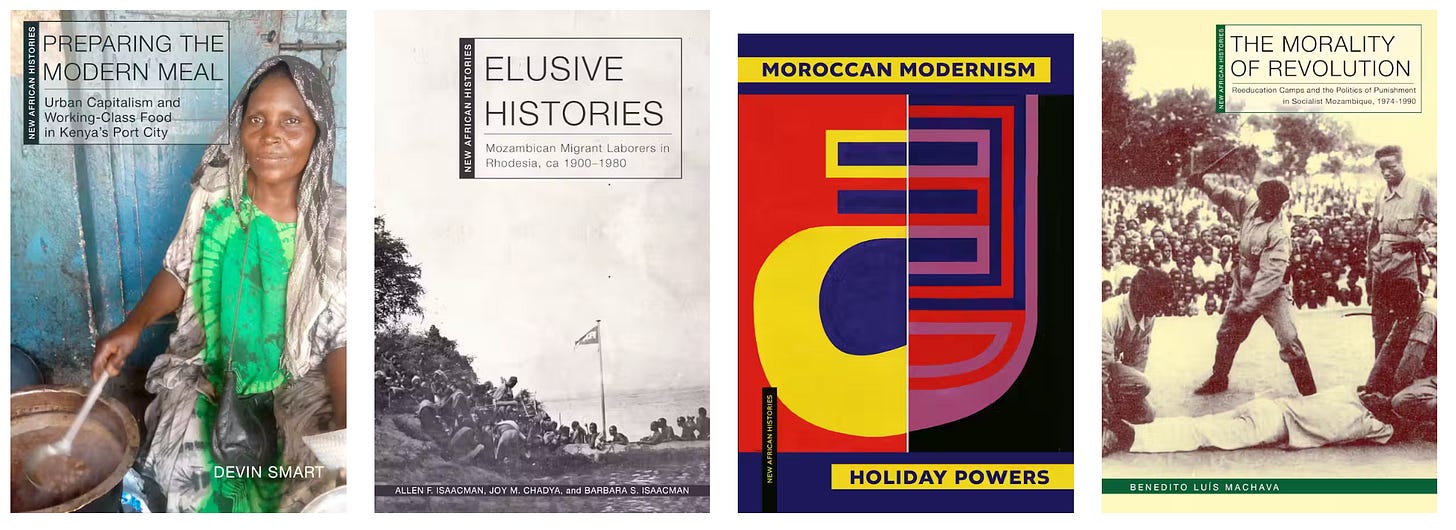

The Ohio University Press is the oldest scholarly publisher in Ohio. Since its founding, the press and its trade imprint Swallow Press, has developed into a leading publisher of books about Africa, Appalachia, Southeast Asia, and the Midwest, as well as on many other topics. The press publishes 25-30 books per year including academic monographs, regional guides, and internationally acclaimed literary works. Some of their special series include New African Histories, Perspectives on Global Health, and Indian Ocean Studies.

To make the publishing process more equitable for scholars of African and Appalachian studies, the press established the Ohio University Press First Book Fund. The fund can be used for any aspect of the revision and publication process, such as manuscript workshopping sessions with major scholars in the field, publicity efforts to strengthen the profile and reach of books by funded authors, or editing and production expenses.

Check out a couple of their recent episodes on exciting books!

Listen to Timothy G. Anderson and Brian Schoen discuss their co-authored book, Settling Ohio: First Peoples and Beyond. They elaborate on the first people who settled Ohio, built civilizations and left an intriguing archaeological record behind, and its growth in the 18th century as Native Americans and Europeans developed trade networks and navigated warfare.

Then check out Burkhard Schnepel and Julia Verne’s discussion about their co-edited book, Cargoes in Motion: Materiality and Connectivity Across the Indian Ocean Drawing from the work of anthropologists, geographers, and historians, this book tells the story of how material objects have informed and continue to shape processes of exchange across the Indian Ocean.

Fast Five: Library of Mistakes

The Library of Mistakes is a free-to-use library located in Edinburgh, Scotland dedicated to financial and economic history.

The goal: “Amid today’s geopolitical and economic ructions, our drive is to extend the understanding of this topic so that both professionals and the investing public can avoid the mistakes of the past.”

Check out their online catalogue here. The Library also maintains an outreach and education program that includes courses and events. Read their schedule for more information.

Russell Napier, the founder and keeper of the library offered to share his top 5 favorite books to introduce NBN subscribers to the important field of financial history:

The Money Game by Adam Smith

A Financial History of Western Europe by Charles Kindleberger

Triumph Of The Optimists by Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh & Mike Staunton

Lords Of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World by Liaquat Ahamed

Money of The Mind: How the 1980s Got That Way by James Grant

Listen to our interview with Russell and check out The Library of Mistakes podcast below!

Graduate Student Corner: Advice with Dr. Susan G. Pedersen

For this edition of Graduate Student Corner, we wanted to share a professor’s perspective on supporting graduate students, and advice to graduate students on how to seek academic support. We were thrilled to discuss this topic with Dr. Susan G. Pedersen. Professors and graduate students alike should read on for her honest and practical answers.

Susan G. Pedersen is the Gouverneur Morris Professor of History at Columbia University. She received the 2024 Nancy Lyman Roelker Mentorship Award from the American Historical Association. More information about the award can be found here.

Q: Why do you dislike the word “mentoring”? What term(s) do you prefer to describe this kind of work?

A: There’s a lot of hierarchy in universities, and some amount of it is necessary, reflecting training and promotion systems that depend on knowledge and expertise. I think it’s best, though, for relationships that cross those lines to be clear and, to a degree, formal. I don’t like the imprecision of the term “mentoring.” I have formal supervisory responsibilities towards my students. I’m their advisor; once they get their degree, I’m their colleague.

Q: Why is supporting graduate students important to you?

A: My aim is to support a scholarly discipline and field in which I, and the students I supervise, all work. I am committed to my field and want it to thrive, which it does by fostering excellent and original work. Scholars begin that work as graduate students; my job is to support their contribution to that common project. Obviously, it’s also fun – I learn from them.

Q: What is your approach to supporting graduate students?

A: Especially now, when the job market is frankly terrible and the universities are under siege, people need to go to graduate school with their eyes open, understanding it may not lead to a tenure track job. My students have gone on to tenured and tenure track jobs all over the world but also to work for museums, libraries, foundations, and governments. So, I try to help them understand their gifts and goals. I also try to be clear about how the academy works. Lots of students begin graduate school thinking it’s about being clever (or, worse, being cleverer than the next guy). That’s, like, 10% of it. Curiosity, good work habits, meticulousness, collegiality, and a love of writing are just as important. It sounds harsh to say this, but anyone who has trouble writing to deadlines should think twice about an academic career, as academic historians write to deadlines their whole lives. But there are other places a love of history can lead you.

Beyond that, I’m an institutionalist. I sometimes have a bad tendency to nag my students, but I try to keep that in check by building institutions (seminars, collaborations, work-in-progress groups), through which students come to see themselves as accountable, not to me but rather to one another and to their fields. Scholarship turns on collegial peer review; the more graduate students learn to work this way, the happier they’ll be. For ten years I ran a graduate consortium in British history with colleagues at NYU and Cambridge to help our students build those kinds of ties, which have persisted even after the project ended.

Q: Do you have any advice for other professors who want to better support students?

A: I’m not great at taking advice from my peers and rather doubt my colleagues want my advice either! I do wish all faculty would answer their students’ emails and do their letters of recommendation in a timely manner. I get too many messages from other people’s students saying x or y won’t answer their messages and could I somehow intervene. This is not my job.

Q: Do you have any advice for graduate students who want to identify and approach professors as possible mentors?

A: You need to know yourself and your needs. I’ve had students who needed lots of advice and students who just wanted to be left alone to get on with it. Either is fine, but advisor and advisee need to agree on the nature of the contract and that it will produce what is needed – a good project and a good dissertation. You need to know about your advisor too. Don’t just reach out to them; do some research. Read their work and talk to their graduate students, who will be honest with you. I would look for three things:

Intellectual compatibility. I have strange views on this, as I don’t think it’s a good idea to be advised by someone very close to your own research interests. After all, you want to become a serious scholar, not someone’s mini-me. Your advisor should find your topic interesting but not know more about it than you do. Instead, look for someone compatible in terms of method and approach. Read a bit of your potential advisor’s work to see whether they use evidence and make arguments in ways you understand and admire.

Reliability. A big part of an advisor’s job is just reading your work and doing letters of recommendation on time. If a potential advisor doesn’t do that (their students will tell you), you should probably think twice. You might want someone who is interesting to talk to but unreliable on your committee but probably don’t want to feel the subjection and frustration you’ll feel if you have to nag them endlessly.

Community. Don’t think of the advisory relationship as purely personal. Most of what you’ll learn in graduate school you’ll learn from your fellow students or other colleagues in your field. I’d look for someone, then, who doesn’t so much focus on you as tries to facilitate such community and contacts. These relationships will sustain you long after you’ve left graduate school (and your advisor) behind.

What to avoid? Well, I would avoid anyone with boundary problems – confuses mentorship and with being a pal, that sort of thing. I’d also avoid anyone who thinks of their students as their intellectual heirs. We all know advisors whose students all work on offshoots of their interests; the European Union has turned this into an industry by giving senior scholars huge project grants and letting them hire PhD students to do various bits of it. I think this is a guaranteed way to limit curiosity and turn out derivative work.

Q: Is there anyone who supported you as a graduate student, or perhaps a colleague now, who you’d like to give a shoutout to as an excellent mentor?

A: I was a graduate student at Harvard in the 1980s. I was jointly supervised by Charles S. Maier and John L. Clive. There were very few tenured women in the Arts & Sciences at that point and the culture of the institution was very different; relationships we would now think inappropriate between male faculty and women students (graduate and undergraduate) were not that uncommon. I feel lucky that both my advisors, and really all the faculty members I worked with (including one woman, the brilliant Byzantinist Angeliki Laiou, with whom I read a field), unflaggingly supported my work and treated me kindly. In retrospect, I feel I walked through a minefield unscathed, because they were the mine-sweepers. I’m really grateful for that.