The Drift

Every year, dozens of new literary mags are born, but few ever make it out of the crib.

The Drift

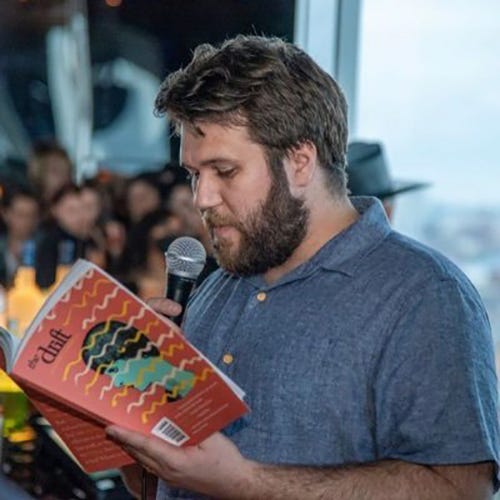

The Drift was founded in the depths of the pandemic and has since become a staple of the New York literary scene. Every year, dozens of new literary mags are born, but few ever make it out of the crib. The Drift’s success hinges on its slow and methodical publication schedule. Only three issues are published every year. The interviews, essays, short stories, poems, and inventive mentions section featuring short, biting reviews bare the handiwork of a skilled editorial team. Last month, Senior Editor Erik Baker appeared on the New Books Network to discuss his recent book, Make Your Own Job. We wanted to learn more about the history and inner-workings of The Drift, so we asked Erik to participate in a Q&A. Read our conversation below:

Q: What is the origin story of The Drift?

A: The 2008 financial crisis, the protracted economic downturn that ensued, and finally the disaster of Donald Trump's first presidential victory in 2016 unleashed a wave of new energy on the American left. The Occupy movement, the Black Lives Matter movement, the #MeToo movement, and Bernie Sanders's presidential campaigns expressed a widespread feeling that American society was fundamentally broken and that mainstream liberalism was not up to the task of confronting the structural problems we confronted. A range of new publications emerged to give voice to these sentiments, and many more established outlets experimented with giving younger left-wing writers a platform.

But by the end of the decade, those of us involved in launching The Drift came to feel that this new intellectual ecosystem was beginning to petrify into a new consensus of its own: the same names repeating the same lines over and over again, despite mounting evidence of the inability of the left of the 2010s to achieve enduring social change. At the same time, we felt a creeping sense of cultural and artistic staleness— the bland homogeneity we increasingly recognize as the signature of our algorithmic age. Our founding editors, Rebecca Panovka and Kiara Barrow, believed this situation created an opening for a new magazine of politics and culture, grounded in the tradition of socialist feminism but committed to intellectual and artistic experimentation and especially to publishing new voices from outside the New York media establishment.

Q: How and why did you get involved?

A: I met Rebecca and Kiara through a mutual friend and found their vision extremely exciting. I was actually the first writer to submit a formal pitch! At the time, I was a graduate student in history, figuring out my place in a profession that increasingly seemed to be in crisis— and that was before Covid and the turn to remote work. I knew I wanted to learn how to write for audiences outside the academy, but I was struggling to find my voice. I was too politically radical for mainstream publications and both socially and geographically outside the networks that seemed to dominate left-wing publishing at that time. So The Drift was a perfect fit.

Q: Can you describe the contents of a typical issue?

A: Each issue begins with a note from our editors and an interview we conduct with a writer or artist we admire; past interview subjects include Jayati Ghosh, Rachel Kushner, Saree Makdisi, Rashid Khalidi, Cathy Park Hong, and Barbara Smith. The typical issue then contains two sections of essays, loosely grouped to create a thematic counterpoint ("Hawks" and "Doves," "Character" and "Plot," to name two recent examples). Then we have a section of short stories and a section of poems.

Q: What are three pieces our readers must read?

A: I think NBN readers will be interested in Jack Hanson's examination in our most recent issue of recent books on Simone Weil. I'll also recommend Piper French's illuminating essay on USC and the troubled relationship of wealthy private universities to their surrounding communities, a subject that has only become more relevant since we published it in 2022. And lastly I will plug Hannah Kingsley-Ma's sparkling story "Underwater," one of my favorite pieces of fiction we published in 2024.

Q: It seems like every year, dozens and dozens of new literary magazines are founded. Why did The Drift succeed when so many others have failed?

A: Luck and timing! We wouldn't be here today if we hadn't been able to develop a roster of extraordinarily talented contributors, many of whom we will be celebrating in our five-year-anniversary issue this summer. At the time, we were worried about launching in the summer of 2020, when pandemic-related supply chain disruptions prevented us from printing our first issue and it seemed like literature was the last thing on most people's minds. But it turned out that people also found themselves with more time on their hands than ever before at exactly the same moment they were looking for new ways to understand a world turned upside-down. And that was an opportunity that we were really able to seize on.

Q: Are there any other newish magazines or blogs you'd recommend?

A: The other main reason The Drift has been able to thrive is precisely because there is such a vibrant community of little magazines right now; we all draw strength from each other's success. Jewish Currents re-launched two years before The Drift with a new young staff and an irreverent attitude; they were something of a proof-of-concept for us. Some of my favorite magazines that have debuted since The Drift launched include Lux, Protean, Hammer & Hope, and the new labor journal Long-Haul.

Q: You recently appeared on the New Books Network discussing your book, Make Your Own Job. What's it about and who should read it?

A: Make Your Own Job is about what I call the "entrepreneurial work ethic," which I argue became the dominant framework for understanding the moral and pragmatic value of work in the United States over the course of the twentieth century. The entrepreneurial work ethic enjoins its subjects not merely to work hard but to work ceaselessly at creating new work, for themselves and others. This practice of making up work is supposed to help people develop new psychological dispositions, like initiative, leadership, and creativity, that many intellectuals and social scientists come to believe are central to human flourishing. Self-help writers and policy experts argue it also helps insulate people from economic turbulence and an ever-more rapidly evolving job market. The rise of the entrepreneurial work ethic, however, ultimately ends up bestowing that increasingly precarious and unequal economy with a patina of moral legitimacy, and also exacerbates the expectations that individuals place on themselves as working people, leading to mounting reports of burnout and exhaustion despite fewer total hours devoted to physically demanding labor. As this description hopefully suggests, I believe the book will be of interest to anyone who works for a living— and especially to anyone who worries the way they work now is unsustainable.

Q: Do you have any advice for scholars struggling to write for a public audience, not just other experts in their discipline?

A: Pitch early, pitch often! My main advice is that writing for audiences outside the academy is a real skill, not merely a mindset shift, and like any skill it takes practice to acquire and perfect. Nothing has improved my own writing more than working closely and collaboratively with hands-on editors— something academics often don't get to experience, sadly. This is self-interested advice, because The Drift is known for our occasionally rather exacting editing process, but I really do think that the writers who improve the quickest are those who rejoice when they open a Google doc and see editors' comments and suggested revisions strewn throughout their drafts.

Subscribe to The Drift’s Substack below: