In this week’s newsletter

The Memory Project’s Piece By Piece is out now

Fast Five with Lorna Gibb

Marginalia with Margaret Echelbarger

Matt Fraser on The Light of Asia

The Memory Project: Piece By Piece

Back in March we shared The Memory Project, a course at Columbia University’s Journalism School in which students learn how to produce a book-length work of narrative non-fiction in one semester. For this project, each student chose a photograph to report on, and crafted a narrative through their findings. The semester has finished, and the Memory Project has published their book! Their book, Piece by Piece: Picking Up What's Left Behind is available for purchase! Check out our previous segment on this great project here, and check out their Substack for more information here.

Fast Five with Lorna Gibb

Lorna Gibb is Associate Professor of Creative Writing and Linguistics at the University of Stirling. Her recently published book Rare Tongues: The Secret Stories of Hidden Languages examines the world’s rarest and most endangered languages.

Metamorphoses by Ovid - I had to translate some verses from this when I was still at school. The change from chaos into order, and the graphic descriptions of physical transformations caught my imagination. I was at a school where casual sexual assault was common (being groped between the legs or having your breasts squeezed in a crowded stairway, for example) and often too afraid to speak about it for fear of the consequences. I willed myself to change, like Daphne, in a kind of prayer, just so I would be left alone. I read the whole book in English and then later with a parallel text worked my way through it in Latin. It’s still the first and only book I’ve read from start to finish in that language. It’s an extraordinary text and, for me, completely without parallel.

The Necklace of Princess Fioramundi by Mary De Morgan - This collection of short fairy stories is very dark but beautifully written. It’s the book from my childhood that I have returned to most often over the years and still always find something captivating in it.

Phonology, A Cognitive View by Jonathan Kaye - I studied with Professor Kaye as a postgraduate and his elegant theoretical framework, as well as his ideas about how language works have influenced the way I understand human communication ever since. If I could only have one linguistics textbook, it would be this (I’m a phonologist by training).

The Complete Poems and Plays of TS Eliot - I am slightly obsessed with Eliot. I think some of his poetry is astonishingly beautiful, and that the gloriousness of it is too often lost by trying to scour it for interpretations.

“Teach us to care and not to care/Teach us to sit still” still catches my breath, as does “Redeem the time, redeem the dream/The token of the word unheard, unspoken/Till the wind shake a thousand whispers from the yew/And after this our exile.” Wow. Just wow.

Savage Girls and Wild Boys: A History of Feral Children by Michael

Newton - This is a book by a longstanding, very dear friend. But that’s not the only reason I’ve chosen it! These six stories are a masterclass in how to weave different accounts together. Michael walked that incredibly difficult precarious line between an almost journalistic recounting and deep empathy. It was the book that somehow gave me confidence to write the books where I try to bring different voices together, because it showed so perfectly how worthwhile it could be.

Put Lorna’s Fast Five on your To Be Read list, and listen to her NBN interview about her brilliant new book Rare Tongues: The Secret Stories of Hidden Languages.

Marginalia with Margaret Echelbarger

Margaret Echelbarger is a behavioral scientist committed to demystifying the hidden curriculum and supporting scholars historically excluded from the academy. Check out her Substack here.

Q: What inspired you to start your Substack?

A: I launched my newsletter in May 2021 because I wanted to provide prospective and current PhD students with the information they needed to thrive in (U.S.) academia–information that is often hidden or inaccessible.

The idea took shape after a successful book drive I organized in September 2020 to distribute copies of Dr. Jessica McCrory Calarco’s A Field Guide to Grad School to students around the world. Thanks to community support, we raised over $8,000. To date, I have been able to send 815 copies of the book to students (primarily in the U.S.) who otherwise might not have had access.

Building on that 2020 book-drive momentum, and encouraged by positive feedback I was receiving on what was then #AcademicTwitter, I decided to launch a newsletter called Let’s Talk Grad School. At about the same time, I was also hosting regular meetings with prospective and current PhD students (between June 2020 and May 2022, I regularly met with students navigating both the PhD application process and, later, the challenges of the first year of their PhDs).

With all these efforts underway, it became clear that I needed a way to make the insights and resources I was sharing more freely available to a broader audience.

At its heart, my newsletter is rooted in a belief that everyone in higher education has a responsibility to demystify the hidden curriculum and redress pervasive inequities. We need a more representative community of scholars producing knowledge and shaping the future of science and society.

This year, I rebranded the newsletter as Marginalia. Although I continue to share insights for prospective and current PhD students, I’m also expanding to include content relevant to scholars at all career stages. The new name is a nod both to my own name (Margaret) and to marginalia (i.e., the notes scribbled in the margins, reflecting my goal of providing informal, practical, and often overlooked advice that supports scholars navigating academic life).

Q: How do you decide what to write about?

A: I try to focus on topics that sit at the intersection of what matters to me, what’s often opaque about the PhD process, and what I think students and colleagues want and need to hear. I don’t just write for prospective and current graduate students; I also write for faculty and others who are committed to demystifying the hidden curriculum and reimagining the academic experience.

As my own career has evolved, so has the way I approach the newsletter. I now write through the lens of being a faculty member who isn’t waiting for tenure to try to bring about the changes she wants to see in higher education. That feels especially urgent now, given the current political climate and ongoing attacks on DEI initiatives, public education, and science funding.

When I write, I aim to share insights that aren’t always found in official guides or resources, and I’m upfront about when I’m offering my opinion versus broader advice. I know I can't demystify everything or claim to have all the answers, but I do my best to be as informative and transparent as possible.

Many of the topics I cover are inspired by conversations with my colleague and collaborator, Dr. Tissyana Camacho. We’ve worked together on several efforts to demystify the hidden curriculum. Most recently, we were invited to speak about this work at the Inclusive Academy Symposium at Princeton, where I was honored to give the talk on our behalf.

I try to balance timely issues, like threats to science funding, with “evergreen” topics like writing personal statements or navigating advisor relationships. I also actively welcome suggestions from students and readers. No topic is off limits.

Q: What is the best book you've read in the past year?

A: One of the best books I’ve read this year is Original Sins: The (Mis)education of Black and Native Children and the Construction of American Racism by Dr. Eve L. Ewing. It was published in February, and it’s an incredible, powerful book that shows how U.S. schools were built not just to educate, but to reinforce white intellectual dominance, to "civilize" Native students, and to push Black students toward lives of limited opportunity and labor.

I was fortunate to attend a conversation between Dr. Ewing and Dr. Mahogany L. Browne at the Center for Fiction in Brooklyn. And although I’ve been to countless book talks (including others by Dr. Ewing), this one was hands down my favorite. The depth, intentionality, and honesty of the conversation made it a privilege to be in the room. Learning from Dr. Ewing through Original Sins and her other creative works has been a true gift.

Q: What are your favorite Substacks and why?

A: Admittedly, I don’t subscribe to many Substacks, but the ones I do are excellent.

One of my favorites is #MHAWS: Mirya Holman’s Aggressive Winning Scholars Newsletter. Dr. Holman is a force. When I’m not writing, I sometimes imagine her sitting on my shoulder telling me to get to work. She’s a clear communicator, studies fascinating topics, and has an unmatched energy that compels you to listen and to act. Through her writing, I’ve learned a lot about holding myself accountable and pushing projects across the finish line.

Another favorite is The Audacity by Dr. Roxane Gay. (Although Roxane Gay doesn’t typically use her academic title in her creative work, it feels strange not to acknowledge it because she is, absolutely, a scholar with a PhD.) Honestly, I would read anything Dr. Gay writes. She could scribble on the back of a bathroom stall door and I’d travel to see it. Her work has helped me learn more about myself, and about embracing complexity in others. She’s incredibly smart, funny, and incisive. She sees the world in ways I can only aspire to. (Also, for anyone looking for more from her, she edited the recently-published book The Portable Feminist Reader.)

Q: Do you have any advice for scholars who might be considering starting a newsletter to share their ideas?

A: Everyone has something valuable to share. I truly believe we all have experiences, insights, and questions that others can learn from, no matter our discipline, career stage, or professional path.

If you're considering starting a newsletter, my advice is simple: be authentic, know your intended audience, and be open to feedback. Think about who you want to reach, but also leave space to discover new readers and communities along the way.

One of the biggest lessons I've learned from writing Marginalia is that you have to find joy and meaning in the act of writing itself, not just in the metrics or audience size. You never know who might find your work helpful, inspiring, or transformative down the line. Some of the best conversations and opportunities I've had came from people I didn’t even know were reading.

Most importantly, your voice matters. The academic landscape benefits from a diversity of perspectives, and newsletters are one way to create spaces for connection, reflection, and change outside of traditional publishing models.

Start where you are, share what you know, and trust that it’s enough.

Matt Fraser on: The Light of Asia

Matt Fraser is a writer and podcaster from Berlin. He is currently working on a new author-first academic publishing venture, Konzept Books, and he writes and podcasts frequently for his Substack, The Ill-Read Millennial.

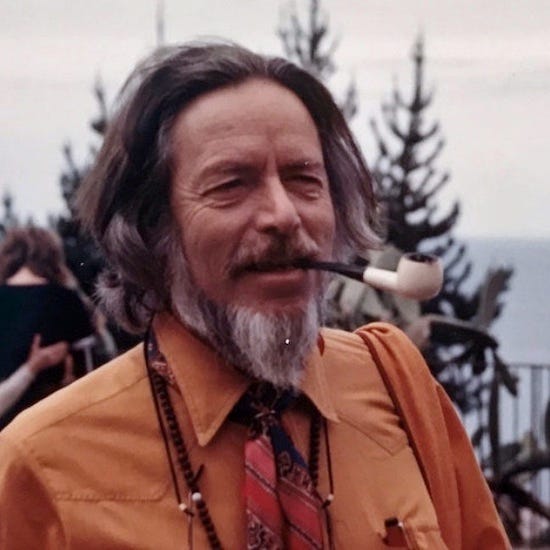

“What is real? Who says? How should I live?” These questions weave throughout Christopher Harding’s book, The Light of Asia: A History of Western Fascination with the East which surveys around two thousand years of East-West cultural, theological and philosophical interaction. In the final part, “Inward,” he looks at the life of Alan Watts (along with psychotherapist Erna Hoch and theologian Bede Griffiths) who, building on a humanist impulse to understand Asian traditions of thought without mythologizing or demonizing, looked eastward away from the turbulence of the early 20th Century in pursuit of concrete answers to these fundamental questions.

Watts is a suitably ambivalent figure to round out the book. Born in T.S.Eliot’s England – an island of buttoned-up administrators against a background of cultural and religious disintegration – Watts was intimidated by the calcified, unimaginative Christianity of the day. After a school friend introduced him to some books on Buddhism, and a ‘moment of bliss’ when he shouted at his thoughts to stop (which they apparently did), Watts began a lifelong attempt to, in Harding’s words, ‘reconcile Asian religions, Christianity and human psychology.’

The psychology part was key; Watts, like C. G. Jung and Erich Fromm, had an intuitive understanding that an individual was deeply shaped by the instincts and subliminal forces of their societies. His relationship to empiricism (unlike Erna Hoch’s) sometimes appears ambivalent; he seems to have welcomed discoveries in quantum physics, for example, because their implications pleased him on a metaphorical level; instead of rigid mass, here was a world made up of fields of possibilities, in which there was no distinction between subject and object, observer and participant – a constant reminder that we are fluid beings whose nature is rooted in potential. To use some of the hippie slang he was fond of later on, why be a ‘square’ when you could realize your potential as a ‘wiggle of light’? The wiggle dislikes straight lines, predictability, steadiness and stasis. England was clearly no place for wiggles.

When war came, Watts headed West to the USA. But before he began his most celebrated period as a popularizer of Eastern thought in California (particularly Zen Buddhism), he trained in the Episcopal church. From this doctrinally liberal perspective, Watts hoped to recover the power of Christian symbology. He was always drawn to the third, elusive figure of the Trinity: the Holy Ghost. This mystical element is often played down in many Anglican traditions in contrast to the concrete Father-Son relationship. But for Watts, the immanent mystery was key and imbued with central concepts in Eastern religion; for example, Hinduism (Atman, the soul, is one with Brahman, ultimate reality). In the end, there were too many philosophical and theological conflicts for Watts to last long in organized Christianity. His embrace of free love and skepticism of doctrine was joined by something else: a sense that his immersion in Christianity had been a lapse into nostalgia. In a world of flux, we look outside ourselves for reassurance. Watts’ mission now was to lead people inward, to embrace their sanctity as conscious beings amongst others, and to remind themselves, in lives of ‘quiet desperation’, boredom and anxiety, of the supreme joy of existence itself. As he moved further West, his thought - though he would never entirely abandon Christ - became increasingly anchored in the East.

His final and most celebrated phase - as a Californian Beat figure, a goat-bearded sage, a ‘philosophical entertainer’ - is at once a natural culmination of his thought and lifestyle, and a long way from the stockbroker belt of the 1920s. From his countercultural base at Druid Heights, California, Watts - ‘never a joiner’ as Harding reminds us - nonetheless attracted an impressive circle of artistic and philosophical outsiders and students inclined to look elsewhere for intellectual and spiritual sustenance after the horrors of their parents’ generation. It was from this period that his audio lectures on which much of his posthumous reputation rests were created; his freewheeling but always fluent talks range from Buddhism, Hinduism and Christianity, to the nature of the self, the relationship between people and technology, and dreams. Harding highlights the contrast between the Freudian view of the ego, as something to be strengthened against the pressures of the world, with that of much of Eastern thought, funneled through Watts:

“The illusion of the ego derived much of its power, Watts argued, from the fact that it was a ‘social fiction’, sustained by societies in whose interest it was to raise purposeful, obedient and self-regulating citizens.”

In an age of ‘Wellness’ and widespread anxiety about the economic and technological aspects of the modern world (these are surely connected), Watts remains a revelatory figure for young people in the Anglophone world who feel, even if they can’t always express, our societal exhaustion. Today, his headmasterly voice has been lent to an advert for luxury cruises, a depressingly common example of the tone deafness (or sheer brass neck) of consumer capitalism, whose deadening effects Watts critiqued with such eloquence. Still, he surely would’ve chuckled. He never claimed to have the answers, but he had plenty of questions, and a refreshingly non-linear way of playing with them. Refreshing, at least, to the Westerners who tune in for a dose of what to many must sound like nonsense, but to others sounds something like pure joy.

It was a real pleasure to interview the author, Christopher Harding, about Watts and several of the other central figures in The Light of Asia. I do hope you enjoy listening.