The Supreme Court

Featuring a curated playlist, episode highlights, and a Q+A with Professor Corey Robin

Happy Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is all about coming together with friends and family and trying our best to avoid messy fights about politics. With a divided Congress, the playing field of American politics will undeniably shift to issues of the Judiciary and judicial appointments. For help getting ready for the kitchen debate, listen to our curated playlist about the American Supreme Court, its most (in)famous judges, and cases that redefined American life.

Scholarly Sources

Corey Robin is Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center.

Q: What are you reading right now?

A: I’m always reading, simultaneously, different books for teaching, scholarship, and pleasure. When I was starting out, I disliked having my attention divided like that. It felt like cacophony. Now I appreciate it. It feels like a conversation.

For teaching, I’m reading Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, which I’ve paired with Plato’s Symposium and Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals. Morrison’s depiction of how Black people reproduce and reinforce white ideas of beauty complicates Nietzsche’s theory of rank and beauty, where the social and aesthetic divisions between noble and plebeian are stark. Her ideas about the freedom of older Black women, who are beyond conventional ideas about beauty, speak to Plato’s idea of the maturation of beauty into virtue and wisdom. Pecola Breedlove’s insanity-driven inner monologue about her blue eyes at the end of the novel mirrors the mania for perfectionism in Plato’s ideal of beauty.

For pleasure, I’m reading Thomas Mann’s letters, which are an irritant and a tonic. The tonic is seeing Mann stick to his bourgeois routines and comforts as the world collapses around him. He loves his new shoes, cigars, trips to the barber, and a fresh shave. I love him loving that. I can never achieve that ease in my life, so I live vicariously through his. The irritant is seeing Mann stick to his routines and comforts as the world collapses around him! Sometimes, his self-care seems like rank solipsism, even narcissism. It makes it hard to get a bead on his personality: his deepest feelings and hurts always slip out of sight. His rants against the Nazis are followed by self-absorbed foolishness (and lack of awareness of how much his wife is keeping it all together for him), which makes you wonder: Who is this guy, really?

I’ve also been reading Nietzsche’s letters to Wagner, which leave me with so much sympathy for Nietzsche the man: how much he suffered, physically and psychically, to write; what a task it was to will his way into his work. I have little patience for his ideas. But I can’t help admiring the pathos and nobility of his character. Also, what it took for him, and from him, to subject himself to Wagner’s discipleship—it’s a wonder he didn’t collapse into madness from that alone! Any graduate student will recognize a type in Wagner—the epic narcissism, the manipulation of younger scholars, how cynically Wagner uses Nietzsche to take on Wagner’s projects and tasks (including shopping for him) at the cost of Nietzsche’s career and well-being. It’s poignant. I love Wagner’s music and loathe Nietzsche’s philosophy, but these letters leave me admiring Nietzsche the man and loathing Wagner the man. It’s an interesting place to be: loving the work and disdaining the man, in one case, and rejecting the work while admiring the man, in the other.

For scholarship, I’m putting the finishing touches on a piece about Keynes. At the last minute, I realized that one paragraph doesn’t make sense. That led me to a massive tome by Stephen Marglin, the Harvard economist, called Raising Keynes. I can’t say I understand all of it, but parts are lucid and helpful in disentangling some of Keynes’s technical claims. Unfortunately, I’ll probably spend hours poring over these arguments and Marglin’s pages, only to realize, later, that none of it will appear in my article. That happens a lot.

Q: What is your favorite book or essay to assign to students and why?

A: I love texts that are challenging enough to require interpretive footwork but not so abstruse that I do all that footwork for the students. I used to love teaching Marx’s Capital, but it requires so much advance layering on my part, that the energy of collective discovery, where students and I figure out the text together, is lost. If students aren’t involved in the collective work of interpretation, it’s not the classroom experience I want them to have.

Here are some books where that doesn’t happen.

The Oresteia: Students love discovering the terror of Clytemnestra, and the way that she weaves her way into power without our realizing it. Aeschylus creates a similar experience for Agamemnon—he only realizes who’s in charge after it’s too late. How Aeschylus writes these characters is an object lesson in the exercise of power. Clytemnestra is such a masterful political animal that we spend hours deconstructing her craft; students always find new patterns in her design.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: From the first paragraph, Douglass demonstrates his command over his story. That command is his story. Just compare it to the absence of command in Henry Adams’s autobiography (The Education of Henry Adams). There’s Douglass’s defiant use of “I”; the specificity of those place names—Tuckahoe, Hillsborough, Easton, Talbot County, Maryland—amid the fuzziness of his date of birth; the sense of historical time lost to the seasons of natural time; the specificity of the labor that is performed in each season. Douglass tells you everything you need to know in that first paragraph: about what’s happened to him and, more important, what he’s done with what’s happened to him. Once students see what Douglass is doing in one paragraph, they’re off and running, looking for his hand everywhere in the construction and design of his narrative.

The Wealth of Nations: I do a lot of advance work for this text, but I love teaching it because it moves so jaggedly from the political to the economic. Smith is constantly translating, or struggling to translate, political concepts into an economic idiom. That struggle forces students to think through the work of an author who is not, like Douglass, in control of his arguments. (Smith gives himself away because he doesn’t know when to shut up; he leans into his own garrulousness and confusion). Instead of marring the text, that lack of control makes it great to teach.

Q: Is there a book you read as a student that had a particularly profound impact on your trajectory as a scholar?

A: Whenever people answer this question, they talk about the books that had a positive impact on them, that they’ve internalized and made their own. I find that answer suspicious.

The books that had the greatest impact are those we loved as students—and have spent our lives trying to get away from. At some point, we came to think that these books are in error and that we were in error for loving them. There’s something discomfiting, morally discomfiting, about our being so besotted with those books; it seems like a deficiency of character. We try to get as far away from them as we can. It’s like a relationship you had when you were younger that you’d like to think you’ve outgrown. But, of course, we haven’t outgrown those books because we spend our lives running away from them, working through our attraction to them.

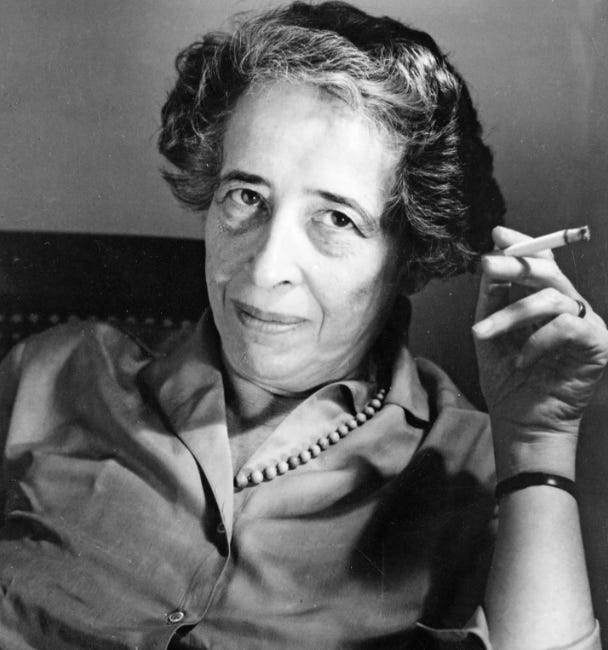

For me, that book is, hands down, Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition. Like many readers of Arendt, I was taken by the grandeur of her conception of the political, especially how political action, whether words or deeds, is different from our other activities—earning money, raising children, teaching students, taking care of our bodies, eating food, making products, writing and thinking.

When I was in graduate school, I got involved in union politics. I often thought with Arendt about my activism. We dealt with conflicts over money, healthcare, and relations between teachers and students—all these activities that Arendt said had nothing to do with politics—yet they were so political, as Arendt defines that term! What is a union contract but a constitution for the workplace? What is a strike but an effort to break with the coercive force of material need? What is a debate over contract goals but a deliberation about needs, something Arendt suggests is not possible? I came to see how our activities in the workplace and the economy are not antithetical to the Greek conception of politics she was enthralled by. They’re just how we do politics in the modern world.

Thinking through her ideas has informed my work on the political theory of capitalism. I’m interested in how Smith’s analysis of economic contracts, for example, repeats Aristotle’s arguments about rhetoric and reason, which, he claims, makes us political animals. Smith’s claim that our possession of wealth, and what we do with that wealth in the economy, determines whether we are seen is similar to what Arendt claims about political action in ancient Greece. That idea—that the economy is the space of appearance—is present in the writings of Brecht, for whom Arendt had a great appreciation. I’m still working Arendt out of my system, more than 30 years after I first read her.

Q: Which deceased writer would you most like to meet and why?

A: None of them. With one exception, every writer whom I respect and admire that I’ve met has been a letdown. On the page, they’re curious and captivating. In person, they’re awkward, I’m awkward. It’s draining. I only want to know them through their writing.

Q: What's the best book you've read in the past year?

A: Ulrich Boschwitz’s The Passenger. It’s a novel about a German Jew, in 1938, trying to flee the Nazis. Instead, he finds himself crisscrossing Germany on trains. It was written in 1942, before people knew how things would turn out, which gives the novel the feeling of daily journalism, of contingency and uncertainty. It’s also a lovely homage to what bourgeois travel and café culture (the main character rides first-class on trains or waits in cafés near train stations) were like for wealthy Europeans in the early twentieth century. That combination—the journalism of dread, the comfort of travel—generates this terrifying effect of menace amid ease, which was the experience of a certain class of European Jews. Rather than focusing on the fear and anxiety of the main character, the book dwells on his bewilderment and loneliness, which is often the experience of people in situations of danger. From the outside, we focus on what we imagine is the fear; from the inside, it’s the loneliness that overwhelms us, the inability to talk to anyone honestly and openly.

Q: Have you seen any films, documentaries, or museum exhibitions that left an impression on you recently?

A: This past weekend, my child, who’s 14, asked me if we could go to the Brooklyn Museum. We used to go all the time when they were younger. Now, not so much. We wound up at an exhibit of Duke Riley’s work, which is based on the trash he’s collected on the beaches of the Northeast—lighters, tampons, plastic bottles, and so on. My wife and I love to walk the beaches in New York—in Staten Island, the Rockaways, Orchard Beach. She looks for sea glass; I help her. The trash we stumble across is overwhelming. This exhibit made me look differently at it. Riley turns tampons into little squids that double as fishing flies and bottles into scrimshaw. They’re lovely.

Last week, as I was preparing to teach Morrison, I wound up watching a documentary about her, The Pieces I Am. Talk about Nietzsche willing his way into work! Morrison got up every morning before the sun rose just to have a few hours to write before her children woke up. She had such a sense of her project and what she had to do to overcome her literary elders. The writer’s will, the stamina of her effort, is fascinating to me. The commentary in the documentary—from scholars like Farrah Jasmine Griffin and writers like Hilton Als and Walter Mosley—is first-rate. It’s one of the few documentaries where I thought to myself, I could show this in class and not feel guilty that I’m giving myself a break from teaching; this would teach students far more than I ever could.

Q: What do you plan on reading next?

A: My email.

Episode Spotlight

In this interview, Myisha Cherry joins Robert Talisse to discuss The Case for Rage. Cherry’s innovative book analyzes how philosophers have feared and misunderstood rage. As Cherry shows, there are different types of anger, some useless and some useful. Drawing on the work of Audre Lorde, Cherry offers a theory of rage that is constructive, useful, and not susceptible to the pitfalls of explosive and unanalyzed anger.

New Books, Links, and Other Things

Joseph Silk, Back to the Moon: The Next Giant Leap for Humankind (Princeton UP)

Siddhartha Mukherjee, The Song of the Cell: An Exploration of Medicine and the New Human (Simon & Schuster)

Heather Hendershot, When the News Broke Chicago 1968 and the Polarizing of America (UChicago Press)

(If you’ve just finished an exceptionally engrossing book, listened to a great NBN episode, discovered a new podcast, or stumbled across an interesting website, please email caleb@newbooksnetwork.com)