NBN Newsletter #15

Featuring a curated playlist about K-12 Education and an interview with educator Nina Leacock

K-12 Education

Education has taken different forms throughout history. Regardless of diversity in instruction, schools around the world have a general purpose of providing everyone with the skills needed to be productive citizens. While sparse and inequitable in its origins, education has become so universal that nearly every country has laws dictating some requirement of compulsory schooling for young people.

In the United States, the origins of contemporary public education can be found primarily in 19th century Massachusetts. As superintendent of education in Massachusetts in 1837, Horace Mann created and promoted a rigorous model for free public education that eventually became a model adopted by many others states throughout the nation.

With the advent of artificial intelligence tools like ChatGPT, K-12 education is facing new challenges. Students can now feed writing prompts into chat bots capable of spitting out full essays in a matter of seconds. Without adequate detection tools, teachers are left only to wonder if their students’ writings are original or simply the outputs of algorithms. Changes in methods and assessments will likely need to take place. In the meantime, the potential death of the essay might lead us to reconsider much of education. One can only wonder what Horace Mann might say to us today as we grapple with the future of pedagogy.

How to See Your Senior Year of High School as a Path to College:

Rachel Steinig and Rodi Steinig, Math Renaissance: Growing Math Circles, Changing Classrooms, and Creating Sustainable Math Education (Natural Math, 2018)

The Economics of Higher Education: A Discussion with David Finegold

Larry Cuban, The Flight of a Butterfly or the Path of a Bullet? Using Technology to Transform Teaching and Learning (Harvard Education Press, 2018)

Decoteau Irby, Stuck Improving: Racial Equity and School Leadership (Harvard Education Press, 2021)

On High School Religious Studies: A Discussion with John Camardella

Heinrich et al., Equity and Quality in Digital Learning: Realizing the Promise in K-12 Education (Harvard Education Press, 2020)

Jay Driskell, Schooling Jim Crow: The Fight for Atlanta's Booker T. Washington High School and the Roots of Black Protest Politics (University of Virginia Press, 2014)

Laura McLaughlin Taddei and Stephanie Smith Budhai, Nurturing Young Innovators: Cultivating Creativity in the Classroom, Home and Community (International Society for Technology in Education, 2017)

Samuel Totten, Teaching about Genocide (Rowman and Littlefield, 2020)

Scholarly Sources

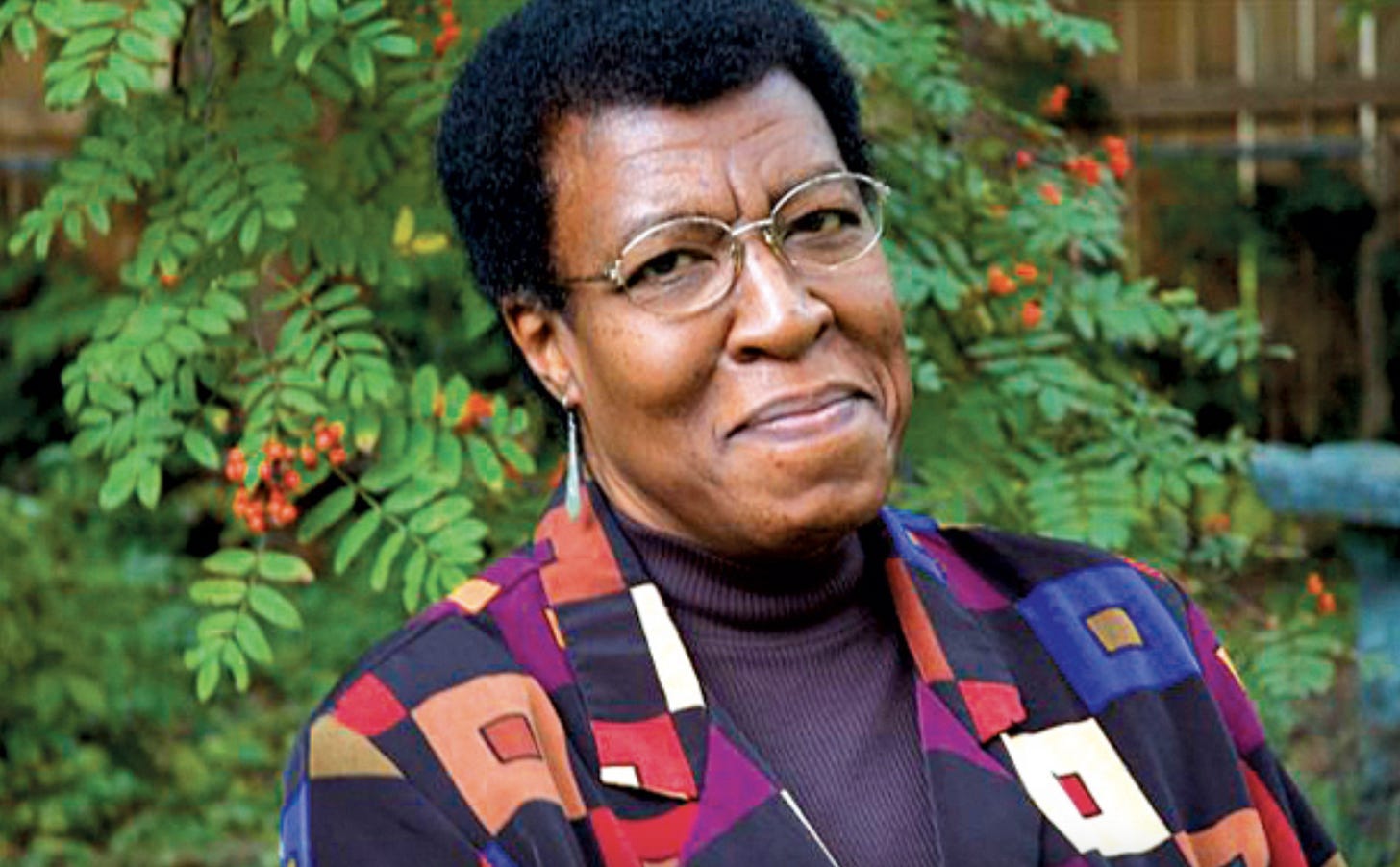

Nina Leacock is a co-founder of the National Capstone Consortium and co-author with Jon Calos of Capstone: Inquiry and Action at School, a book for teachers of high school capstone programs.

Q: What are you reading right now?

A: I am rereading Octavia Butler's Xenogenesis trilogy. I first read my favorites among Butler's novels when I was a teenager and they were being first published. Much later, I started teaching her work. By then, Xenogenesis had been reissued as Lilith's Brood and there were a number of interesting critical interpretations that helped me think about what it means to read Butler in a classroom. Marisa Parham has an essay about Kindred that opens with a teaching scene. Her discussion of that scene fascinated me and changed my own approach. J. Adam Johns has a series of essays about Butler's relation to sociobiology. You can see his thinking about Butler evolve over a time period in which we are all thinking about society in increasingly biological terms. Now I am writing a book about teaching high school that includes Xenogenesis. It's an opportunity to look back on how the reception of Butler's novels has unfolded across the decades.

A few days ago, I was talking with a friend about the paintings of Agustín Lucho Pozo Gálvez. Lucho's work seems to clearly be in the tradition of abstract expressionism—but the paintings are not truly abstract. There are elements in them that engage the viewer's attention as if they represented real things, an apartment block, for example, or a human figure. But when you look more closely, they are not representational either. The painting won't let you conclude, "oh, that's a building." The paintings are neither abstract nor representational. Butler's work seems like that to me. The Oankali (and the humans) in Xenogenesis engage the reader's attention as if they represented real groups in American history. But her story is also not like our history. The Oankali are ideas more than characters. It provokes you to think. By the end of Dawn, the first book in the trilogy, Lilith is not human anymore either. What do you do with that?

Q: What is your favorite book or essay to assign to give to people and why?

A: I have assigned the essay "Peeling Potatoes" by Greg Sarris to nearly every high school class I've ever taught. I have given the essay collection Keeping Slug Woman Alive, to which this essay serves as a prologue, to a number of friends who also teach. An essay on scholarly method, but also on why method is not enough, "Peeling Potatoes" introduces the work of scholarship to students with all of its contradiction and transformative potential. There is no superficial misunderstandings of objectivity, no misleading tone suggesting that the work is going to be easy or that the student-scholar won't be changed by it.

Q: Is there a book you read as a student that had a particularly profound impact on your trajectory as a scholar?

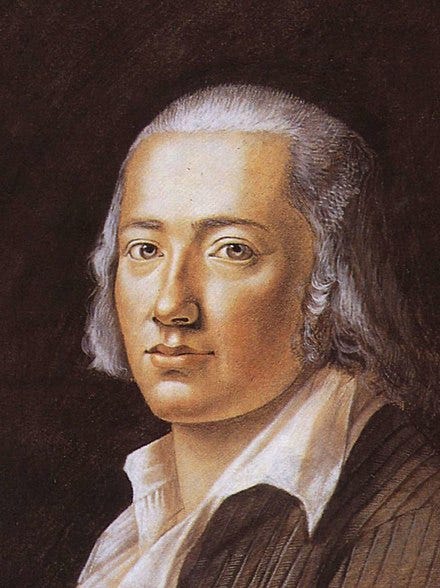

A: There's an idea that had a profound impact on my trajectory as a reader. I found it over and over in different authors: Octavia Butler, Greg Sarris, and for me early on, in Goethe and Friedrich Schlegel, and later on Plato. The idea is that reading is an encounter between me and the text. I am never reading to become more like the author or protagonist, nor am I reading to adopt anyone else's opinions. I am reading to become more myself. So whether or not I "approve" of what I read does not matter. What I have to experience is my reaction, and what I have to own is my response. The authors I mention above throw me back on myself as much as they draw me into the work.

Novelist Alfred Andersch wrote a description of Ernst Barlach's sculpture the Lesender Klosterschüler—the Reading Student, or better, the Novice—that captures the reader's attitude for me. The sculpture is described through the eyes of the novel's protagonist, Gregor, who comes across it in a church.

And then all of sudden he noticed that the young man was different. He was not held spellbound. He wasn't even immersed in his book. What was he actually doing? He simply read. He read attentively. He read precisely. He even read with intense concentration. But he read critically. He looked as though in every moment he knew just what it was he read. His arms hung down, but they seemed ready at any moment to lay a finger on the text to show: that is not true. That I don't believe. He is different, Gregor thought, completely different. He is lighter than we were, like a bird. He looks like a person who might at any moment close his book and get up, in order to do something completely different.

I keep a picture of the Lesender Klosterschüler above my desk to remind me of my aspiration to simply read.

Q: Which deceased writer would you most like to meet and why?

A: It seems unkind to bring any dead people back here. I would like to die and go into a book, however.

Q: What's the best book you've read in the past year?

A: After some consideration, I have adopted Friedrich Schlegel's opinion that there is no need to evaluate texts for quality—or at least to avoid talking about evaluation much. Either you read it or you don't. So maybe I should evaluate my own reading, instead of the books. I've had a better-than-average year with the poems of Hölderlin. More than thirty years ago, I became very interested in Sophocles' Antigone. Because of that interest, I read a short book by Martin Heidegger that is substantially about Antigone, but also about the poem named in its title: Hölderlin's Hymn "The Ister." The book was both difficult and fascinating. I have memories of sitting in a park with it, learning how to concentrate. An initial interest in Hölderlin came along as a sort of by-product of that experience. I was interested, but I could not get anywhere. Nothing that I already knew about reading poetry helped me with Hölderlin. The life of a high school teacher lends itself to long projects with short, difficult texts like these. During the school year, you don't have time for texts that are difficult and also long. But you can read one poem on a Saturday morning and mull over it through the week.

Hölderlin became a sustaining project for me across the many years I spent teaching high school. I was reading him for my own learning, not for purposes of teaching or even talking about the poems with anyone else, so there was a wonderful purposelessness to the reading, at the same time as it continued to be difficult. Now it is a pleasure to have the memories of so many years as I return to poems that never become more "familiar" even if I have a few more or less memorized by now. When I read the notes written by the long-ago younger me, I am also amazed at how much of Heidegger's book I was able to engage then, and equally amazed at how much more I can engage as I reread now. Hölderlin is a teacher of patience. If you just keep reading, things come to you in their own time.

Q: Have you seen any films, documentaries, or museum exhibitions that left an impression on you recently?

A: The paintings of Agustín Lucho Pozo Gálvez (including his one-man show in 2020) have left and are leaving an impression. Abstract expressionism didn't die with my parents' generation, and its new expression in Lucho's work is disturbing and wonderful to me. After I read Andersch's description (see above), I wanted to see the Lesender Klosterschüler for myself. I was young, it was a pilgrimage. My childhood friend Anja and I walked a long way to find the chapel in Güstrow which had been desacralized and made into a museum just to house this one holy-sober reader. When we asked for directions, people in the neighborhood had never heard of Barlach or the Novice. That's how it is. The encounter between the viewer or reader and the work can be far to seek. I can imagine someone making a journey to see one of Lucho's big canvases, while I found him in my own backyard—so to speak.

Q: What do you plan on reading next?

A: No plans, just reading.

New Books, Links, & Other Things

Richard Barrios, On Marilyn Monroe: An Opinionated Guide (Oxford UP, 2023)

Robin Steedman, Creative Hustling: Women Making and Distributing Films from Nairobi (MIT Press, 2023)

Enquist et al., The Human Evolutionary Transition: From Animal Intelligence to Culture (Princeton UP, 2023)

David Rothenberg, Whale Music: Thousand Mile Songs in a Sea of Sound (MIT Press, 2023)

Amy B. Zegart, Spies, Lies, and Algorithms: The History and Future of American Intelligence (Princeton UP, 2023)

Interested in Becoming an NBN Host?

Are you interested in becoming a New Books Network host? Are you a professor, graduate student, or an expert in a particular field of study? Apply to become a host to help support our mission of creating a free and accessible academic library!