To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause: The Many Lives of the Soviet Dissident Movement is an extraordinary history of political dissidents in the Soviet Union. Twenty-five years in the making, historian Benjamin Nathans calls it an “an exercise in extreme delayed gratification.” In the forthcoming book (August 13th), Nathans examines dozens of intellectuals who sought to break the Communist Party’s authoritarian hold over the Soviet people. Starting in the 1960s, a small but highly educated cohort began to fashion their own rights movement resonant with the American civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King Jr. Numbering in the tens of thousands, the Soviet dissidents primarily operated in secret. Their main form of dissent involved producing and disseminating samizdat, literature banned by the Communist Party. In total, more than 10 million Soviet citizens read or listened to works produced by dissidents. Nathans argues that the Soviet dissident movement was not animated by an opposition to communism but rather a struggle to compel the Soviet Union to live up to its stated ideals and laws. This analysis highlights the homegrown nature of the dissenters’ views, instead of the Western-centric interpretation that sees the Soviet dissidents as merely capitalists born on the wrong side of the iron curtain.

To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause focuses on the most active dissidents. While most scientists did not dissent, a large segment of the dissidents were scientists, mathematicians and computer engineers. Of the most involved, more than half of the dissidents had Jewish heritage; though, the vast majority of Soviet Jews (more than 99%) were not involved in the creation or distribution of banned texts. What, then, was the common thread that ran through the lives of the dissenters? According to more than 150 book-length memoirs studied by Nathans, nearly all were traumatically victimized by the KGB and its Stalinist forerunners.

The KGB attempted to coerce thousands of people to inform against their family, friends, and colleagues. Those targeted frequently held ideals aligned with the cause of socialism. The KGB’s attempts to compromise them conflicted with their ideals, inspiring them to rebel. While many dissidents would go on to achieve renown in the Western world, it was seldom a preference for capitalism over communism that inspired their dissent. Rather, the source of their dissent was tied to ethical concerns regarding their personal ties and moral beliefs.

Alongside dissident memoirs and other samizdat, Nathans mines the archives of KGB branches located in the non-Russian Soviet republics. To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause is built on the foundation of hundreds of interrogation transcripts that show in detail how the KGB sought to compromise individuals. Political dissent was not easy, and those willing to fight against authoritarianism often possessed character traits that marked them as obdurate and inflexible.

An important question that Nathans seeks to answer is why the dissident movement began in the 1960s instead of earlier. Surely there were dissenters against Stalinism, but the sheer terror and political violence inflicted by his government during events like the Great Purge from 1936-8 made it almost impossible to fight back. Following the interpretation of political philosopher Hannah Arendt, Nathans argues that the death of Stalin marked a transition from totalitarianism to authoritarianism. Specifically, this meant that the Communist Party would no longer apply tactics like political terror and the random targeting of civilians for interrogation. After 1956, the KGB sought only to arrest or interrogate those that they genuinely suspected were engaged in dissident acts. Under Stalinism, the only real form of dissent that wouldn’t lead to imminent death was silence. In the new environment, dissidents could operate with fewer threats hanging over them.

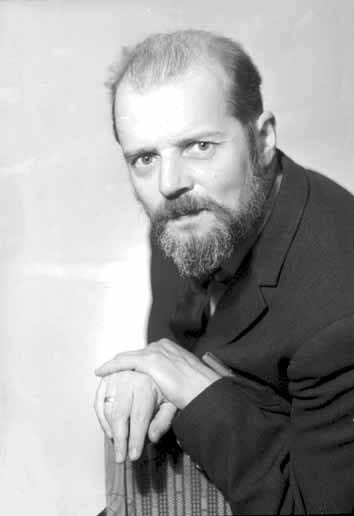

In the 1960s, the greatest concern shared by the dissidents was a relapse into the horrors of Stalinism. Alexander Esenin-Volpin, a mathematician and son of the Russian poet Sergei Esenin, spent several years incarcerated in the early 1950s for allegedly writing anti-Soviet poems. If not for his famous father, he likely would have been killed. Luckily, he was held in a psychiatric prison and then exiled to Kazakhstan. Upon his return after Stalin’s death, he became involved in the nascent dissident movement. Esenin-Volpin hit upon a brilliant approach which would soon be taken up by other Soviet dissenters: critique the Soviet Union for its failures to live up to the ideals of communism. In 1965, after the arrests of two writers, Esenin-Volpin organized one of the first public demonstrations against the government. The demonstration’s focus was on adherence to the Soviet Constitution, which guaranteed a slew of rights such as the freedoms of speech and assembly. As Nathans explores, the dissidents almost universally believed that the Soviet Union would never collapse. Instead, they believed that their best hope was for the Communist Party to reform itself and make good on its promises.

Thirty years after the start of the dissident movement, the Soviet Union would disintegrate quickly, unexpectedly, and with relatively little bloodshed in 1991. Though it is difficult to say exactly why its dissolution occurred this way, there is a powerful argument that the dissident movement helped sway hearts and minds to the view that the Soviet Union would never live up to its ideals. By the time the empire was teetering, its defenders were few and far between.

Another possibility is that the violence expected from the Soviet Union’s collapse was not avoided but rather delayed. Vladimir Putin, Russia’s authoritarian ruler, was famously an agent of the KGB. In the last days of the communist government, Putin dedicated himself to destroying secret KGB files in East Germany. In recent years, he has invested great attention to controlling, rewriting, and destroying historical memory. Just two months prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Putin shut down the Moscow-based human rights organization, Memorial, dedicated to documenting the political terror wrought by the Soviet Union during Stalin’s long and brutal tenure. For their work, Memorial received the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize. The stories of Soviet dissidents are an inspiration to the ongoing fight against authoritarianism in Russia and elsewhere. To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause documents the qualities required and strategies necessary to resist oppressive political entities.

Listen below to a conversation between Marshall Poe and Benjamin Nathans about this excellent new book.

Apple Podcasts

Fascinating context. Beyond the world of ideas are the lived experiences of beleaguered people: "According to more than 150 book-length memoirs studied by Nathans, nearly all were traumatically victimized by the KGB and its Stalinist forerunners."