The Art of Writing

“How can we use language in a way that resonates with our audiences? And how can we wield writing as more than just a tool but also as an opportunity to find some sort of beauty in expression?”

-Nicolas Baird

In this week’s newsletter:

Follow us on Bluesky

Scholarly Sources with Joe Pierre

Meet the Presses: The Hong Kong University Press

Graduate Student Corner: Dissertation Writing Tips

Follow NBN On Bluesky

We are on Bluesky! Follow us to learn more about recently published episodes, recent publications from our partner University Presses, and other book news! Click here to find our page, or search @newbooksnetwork.bsky.social

Scholarly Sources: Joe Pierre

Joe Pierre, M.D., is a psychiatrist with nearly 30 years of clinical experience and academic expertise in false beliefs. He is a Health Sciences Clinical Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of California, San Francisco.

His recent book False: How Mistrust, Disinformation, and Motivated Reasoning Make Us Believe Things that Aren't True illuminates the psychology of false belief that lies at the root of contemporary media mistrust, science denialism, and political polarization.

Q: What are you reading right now?

A: Technically, I'm not in the middle of anything right now. Generally speaking, I read academic journal articles more than anything else and don't find a lot of time to read books these days. But the past year has been an exception— I've read Hannah Arendt’s classic The Origins of Totalitarianism, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt’s How Democracies Die, Ruth Ben-Ghiat’s Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present, Timothy Synder’s On Tyranny and On Freedom, Anne Applebaum’s Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism, Masha Gessen's Surviving Autocracy, and Jason Stanley’s How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them. I guess you could say I've been fixated on a theme. I also recently read Jonathan N. Stea's Mind the Science: Saving Your Mental Health from the Wellness Industry.

Q: What is your favorite book or essay to assign to give to people and why?

A: Of the ones I mentioned and aside from my own, Jason Stanley’s How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them. It does the best job of succinctly explaining what's going on in US politics right now.

Q: Is there a book you read as a student that had a particularly profound impact on your trajectory as a scholar?

A: In college, Huston Smith's The World's Religions and Freud's The Future of an Illusion made an impression. More recently, Stephan Lewandowsky's journal article, "Beyond Misinformation: Understanding and Coping with the “Post-Truth” Era," was probably the most impactful on my recent work.

Back in my student days, I read a lot more fiction— especially short stories—that fueled my desire to write. I've had my JD Salinger, Kurt Vonnegut, Kafka/Camus/Dostoevsky, and Charles Bukowski phases. I'm an enduring fan of Raymond Carver and loved What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Each story was like a punch in the gut. I had a similar experience reading Peter Carey's Collected Stories. The late radio legend Joe Frank has also been a huge influence.

Q: Which deceased writer would you most like to meet and why?

A: I don't usually fantasize about meeting people who aren't alive since it's not possible, but that one's easy— I'd love to have a drink and talk with whoever wrote the Bible.

Q: What's the best book you've read in the past year?

A: Same answer as #2— Jason Stanley’s How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them.

Q: Have you seen any films, documentaries, or museum exhibitions that left an impression on you recently?

A: Not so much recently, but some of my favorite films are The Seven Samurai and Grizzly Man. I had a few minutes of fame as a featured expert in the documentary Behind the Curve about flat-earthers. A few years ago, I saw some paintings by Franz Kline up close in an exhibition— very powerful imagery that's stuck in my mind.

Q: What do you plan on reading next?

A: Not sure, but I have a big pile of fiction (literally) that I'd love to catch up on. I'm a Haruki Murakami fan, so the one I'm most eager to read is First Person Singular.

Q: Who should read False?

A: Everyone, of course! But definitely anyone that has recently wondered, "why can anyone believe that!!?"

Listen to his full NBN interview to hear Joe Pierre discuss his book!

The Hong Kong University Press

Since its establishment in 1956, The Hong Kong University Press has grown from a publisher of only a few titles, primarily studies done by the University’s own faculty, to one that releases up to 50 new titles a year from leading scholars around the world. The HKU Press draws on their unique position in Asia to publish scholarly work that examines, critiques, and celebrates Asia’s place in the world. With authors in North America, Europe, Asia, and beyond, The HKU Press maintains a global outlook. A distinctive aspect of The HKU Press is the multilingual publication program that dates back to its very beginning. They are committed to making Chinese in all its varieties more available to English speakers and vice versa. About 3/4 of all books are published in English, and 1/4 in Chinese.

The HKU Press publishes books from the full spectrum of academic disciplines, and has become renowned for publications in cultural studies, film and media studies, and Chinese history and culture. Check out some of their new books including Socializing Medicine: Health Humanities and East Asian Media, Surrealism from Paris to Shanghai, and A New Documentary History of Hong Kong, 1945–1997. You can browse their collection of newly published books here.

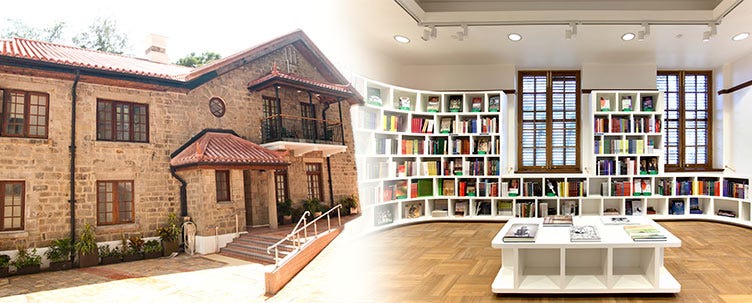

If you are in Hong Kong, check out The HKU Press Bookshop at Hong Kong University where you can find more than 5,000 books published by The HKU Press and partner presses. The bookshop is on the ground floor of a heritage building originally constructed in 1923 to accommodate senior staff who worked at the Elliot Pumping Station and Filters. Unique architectural features that you can admire while visiting include multi-casement windows, rough-honed granite walls and French windows.

Dive into some of the NBN interviews with authors of HKU Press books!

In 1842, the Qing Empire signed a watershed commercial treaty with Great Britain, beginning a century-long period in which geopolitical and global economic entanglements intruded on Qing territory and governance. Previously understood as an era of “semi-colonialism,” Stacie A. Kent reframes this century of intervention by shedding light on the generative force of global capital. Tune in to her fascinating interview about Coercive Commerce: Global Capital and Imperial Governance at the End of the Qing Empire.

Listen to Francisca Yuenki Lai discuss, Maid to Queer: Asian Labor Migration and Female Same-Sex Desire. Based on participant observation and in-depth interviews with Indonesian domestic workers in Hong Kong, Francisca explores the meanings of same-sex relationships to these migrant women, documenting the intersections of domestic work, labor migration, race, and religion on the sexual subject formation.

China has one of the largest queer populations in the world, but what does it mean to be queer in a Confucian society in which kinship roles, ties, and ideologies are of paramount importance? In his book, Queering Chinese Kinship: Queer Public Culture in Globalizing China, Lin Song analyzes queer cultures in China, offering an alternative to western blueprints of queer individual identity.

Subscribe to The HKU Press Channel to listen to all of their compelling new interviews!

Graduate Student Corner: Dissertation Writing Tips

For this edition of Graduate Student Corner we interviewed one graduate student beginning their dissertation and another who is almost finished. We invited them to give advice to other students at varying stages of dissertation writing.

Nicolas Baird is a paleobiologist, artist, writer, and performer living in New York City, in their third year of study for a doctorate in Earth and Environmental Sciences at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. They are a partner student of the American Museum of Natural History’s Richard Gilder Graduate School, based in the Division of Vertebrate Paleontology. They also co-direct the Institute of Queer Ecology, a continuously evolving collaborative organism that creates and commissions artworks as tools for building multispecies futures.

Christine Prevas is a Ph.D. Candidate in English and Comparative Literature, with a focus in gender and sexuality in contemporary horror media. Their interests range from literature to film to video games, with a particular interest in experimental form and non-traditional and collaborative forms of digital media narrative. Their dissertation "Architectures of Gender in the American Haunted House" utilizes architectural theory to examine the ways in which gender is produced, constructed, or disrupted by the built environment of domestic spaces.

Do you have any advice for grad students, generally maybe in their first year, first couple of years, just general advice you want to give?

Nicolas: I’ve noticed that in the sciences it’s more common for undergrads to go directly into graduate school, and I think that lack of a gap can come along with this intensity and heaviness around academic validation that allows it to fill up more space than it needs to. I took several years off between undergrad and starting my PhD, and I'm grateful for that time because I feel like I have a bit of psychological distance from that weight. It’s a little easier to focus on doing research and enduring the long road to the dissertation without worrying so much about smaller bumps along the way. My two-part advice, then, is: (1) grades don’t matter, and (2) try to build community and friendships outside of school as much as you can.

Christine: Have a hobby! Whatever the hobby is, have something outside of grad school that can help anchor you and define you and give you some sense of worth or excitement outside of grad school.

Q: How has your work as an artist informed how you approach dissertation-writing and vice versa?

Nicolas: I think coming from an arts background into a STEM field has both helped and hurt. In my creative work, I use words a lot, both in poetry and prose, and that practice feels like it comes from a very personal place. It’s intuitive and I enjoy playing with meter and rhyme, how words work together and resonate through metaphor. But in academic writing, especially scientific writing, I need to turn on a totally different way of using my brain, even though it’s still “words to paper” in the end. It’s definitely been a challenge to bring that creative mode of writing into the tight structures and formalism of scientific/academic writing— and to figure out when to let it go.

Q: What tips do you have for anyone that's about to start writing their dissertation?

Nicolas: Give yourself permission to put any thought you have onto paper. It may or may not be useful later, but it deserves to be written down and saved in this personal archive that you can draw from later. It’s been helpful for me to recognize the little voice in the back of my head that tells me what I’m interested in, what questions might hold my interest for a while, so I always keep a little notebook in my bag. As soon as I can, I copy out anything I write in it into a text doc on my computer. It’s a way of keeping track of little ideas and collecting them, even if they don’t turn into anything substantial.

Christine: Find a writing structure that works for you and allows you to be a human beyond your research. At the same time, acknowledging that deviating from the routines that you've set before isn't a failure. It’s an opportunity and it can help make those transitions when they need to happen again feel more graceful and less desperate. Try new things and see what works for you, then do it until it doesn’t work for you anymore and feel free to change it up.

Q: What did you do to prepare to write your first chapter?

Nicolas: For years, my writing method was something like: write a paragraph, or even a sentence, and then edit it before moving on to the next. I liked to write this way because I felt that if I knew what I’d done was ready to go, I didn’t have to look back at it or worry about it. When I started writing my first chapter, though, this approach suddenly didn’t work for me anymore. Instead, I found I had to do a lot of brainstorming, writing out all these messy ideas in one unwieldy, completely unorganized document, then spend weeks sorting through the mess and bringing it into a readable state. This way of going about writing meant I spend much more time editing, but the brainstorming really helped me articulate what the actual questions I was trying to ask were in a way that I don't think I could have done with my more linear approach. In dissertation work, you’re often figuring out the questions as much as the answers, and you have to see what works best as you work in this new mode of thinking!

Christine: When writing my Masters thesis, I was able to find a writing process that worked well for me. I worked starting at 9am every morning, then after leaving for lunch I would not look at my writing again the rest of the day. I found that even though I wasn’t actually writing, I was still subconsciously working through my ideas during the rest of the day. But I was also able to do things that felt energizing in other ways and keep a sustainable work-life balance. When I started the dissertation I wanted to make sure that I could have a writing structure that felt sustainable. I sat down and I sketched out what my five chapters were, when I wanted to graduate, the deadlines that I would have, and went from there to determine how much time I had for each chapter. Now that I’m at the end, that schedule hasn’t 100% stuck, but it has been a good baseline to make sure that I wasn’t overworking myself, and could still be flexible in times when I couldn’t keep to my regular writing schedule. Some weeks of graduate school we are less busy, but during other periods more is asked of us. So, making sure that I had extra space in my schedule where I could get my daily writing done and still be able to focus on other things like revising an article, grading, job applications was useful to keep myself from working too many hours to get everything done and feeling overwhelmed. I think building a schedule that is sustainable and that has space for moments of overflow built-in helps.

Q: What has been helpful to you in terms of organization, time management and the nuts and bolts of getting everything done?

Nicolas: I go on walks. It’s not always easy to make time during the day and it’s hard to leave my desk in the middle of the week without feeling a little like I’m playing hooky, so I’ve started taking voice recordings as I walk. I just ramble about my research and look for birds and feel the sun or the rain or the wind. When I’m back at my desk, I generate a transcription of the recording and copy the text into a document. It helps me work through the early stages of ideas that would’ve been painful to sit down and write out in silence.

It’s also been really helpful to have others in the writing studio to talk about the writing process (without getting into the weeds of the content), share concerns about productivity and motivation (or lack thereof), and learn from each other as we all go through the dissertation-writing process. Talking to students outside my department has also been helpful to think about connections between ways of thinking and to approach my own research with a new perspective.

Christine: If I can sit down at the computer at 9am I can usually write for 3 hours. So I try to stick to that schedule, but I've built habits that help allow for that variability. One thing I do is, at the start of every week I lay out all my tasks for the week and I try to make sure as I plan out the week that those tasks hit a variable set of energy commitments and time commitments. So when I have days where I have a lot of energy I can tackle the bigger, more intellectually engaging tasks and on other days where I have less energy, less bandwidth I do a task like managing my citations, or crossing some busywork off of the list. I think moving from setting daily goals to setting weekly goals helps build more of that flexibility so that I don't put the pressure on myself every day to be a certain level of productive.

It’s also been really, really helpful to have a designated place where I know I am going to write at a certain time. I think that's been really helpful in building that structure for myself so that even on the days that feel the worst, where I know I need to get work done, just getting to the spot and sitting down in front of my laptop is already three quarters of the battle.

Q: How do you manage teaching and writing at the same time?

Christine: This advice was given to me by a colleague of mine: teaching is something that will expand to fill the time you give it. So you have to set strict limits on when you're doing teaching stuff and when you're not. When I first started teaching I designated days that I would look at teaching stuff, and days that I would do my own work. That was really useful. Really carefully partitioning off time that I allow for each task is useful so that when things start to overspill those boundaries, there's space for them to overflow into.

I also think that what's been helpful to me is to think of teaching as something I get to do rather than something I have to do. This year has been interesting because as I've been on the job market, teaching has been the thing that really energizes me. My research has fallen by the wayside as I've been working on job materials, and as I'm approaching the end, and I really didn't touch my dissertation for most of the fall, and the whole process has been demoralizing and exhausting. But when I walk into the classroom, and my students are there, and they're excited to be there, that's the thing that's like, oh right, this is the reason I'm doing this.

Q: How do you try to maintain a healthy work-life balance?

Nicolas: I pendulum-swing. I'll go through tides of really intense working, and then a week of not really getting a lot done. I’ve had to learn to be okay with that. The balance seems to even out over time. Noticing that, being aware it’s happening, and accepting the longer-term balance has been really helpful for my mental health. I also try to always have a book for pleasure to read on the subway :)

Christine: I try to think about graduate school as if it were a 9 to 5 job. I don’t touch graduate school work after 5pm or on weekends unless a student is having an emergency.

Q: Do you have any advice for people that are at a similar stage as you right now? Close to the finish line and also juggling job applications.

Christine: To be honest, compromise. A lot of what I'm doing now is taking out pieces that feel important to me because I don’t have time to get my committee to accept them in this work now. Knowing that the project has a future beyond the dissertation, and that some things that aren’t fitting in right now can eventually make their way into the book. I also think that flexibility in writing structure and time management has been crucial. Finishing the dissertation is emotionally a difficult process. I went from feeling fairly sure of myself and confident in my academic abilities, to now I feel like a feral caged raccoon who doesn’t know where they are. I don’t know that there's a great way to avoid that happening because of the nature of the process. So, I think maybe just going into it knowing that feeling this way could happen is enough to help you have perspective and know that it’s not only you feeling this way. It’s the nature of things.

Q: Do you have any advice on managing feedback?

Christine: I hate feedback, and I hate revision. I take feedback very personally, and I do not handle it with grace. I’ve found it helpful to have a feedback buddy. When we get feedback, we give it to each other, and we each rewrite it for the other person. So we both get our feedback in a friendlier voice and get to talk through it with each other from a less emotional place. It helps me detach from this question of how my advisors feel about me, and then it’s easier to process and turn into practical advice. I also want to encourage people to push back and advocate for the things that they do think are important. Try to think of the chapter meeting less as a dressing down and more as like a conversation. When your committee asks why you did something, you can explain why you did it, and why it matters. They still might hate it, but maybe not, right? And then you both get a better sense of how the other is thinking of, and understanding the project.

Q: Do you have anything else you want to share?

Nicolas: Well, I guess I have an open question. I’m still in the middle of my PhD, and there’s something I’ve been trying to figure out: I care a lot about words–how they sound and how they look on the page, how they help us frame and articulate our thoughts, and how our thoughts evolve as we think and talk and write. How do you attend to all of those different ways of engaging with words as an academic writer?

I’m trying to produce this sort of scientific type of writing, but I want it to be beautiful and I want the models and metaphors I use to be rigorous and true. I don’t just want to use words as bricks, but to be attentive to the evolution and climate of each word. How can we use language in a way that resonates with our audiences? And how can we wield writing as more than just a tool but also as an opportunity to find some sort of beauty in expression?