HBCUs, the U.S., and Us

Featuring an interview with Dr. Deondra Rose, an essay by Leo Bader, and a breath-taking, new encyclopedia.

HBCUs, the U.S., and Us

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. would likely not have lead the American Civil Rights Movement if not for his undergraduate experience at Morehouse College. It was at Morehouse, at the time an all-male, all-Black college, that he was mentored by the school’s president, Benjamin Mays, and inspired to become a Baptist minister. In the segregated South, Morehouse was a beacon for Black men looking to succeed, offering them opportunities for upward mobility otherwise unavailable. The school’s focus on social and political engagement shaped a generation of young leaders who sought to make America a more equal and just country. Students and alumni like Dr. King went on to shape a political movement that gave schools like Morehouse a new moniker: HBCUs or Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

The history of HBCUs is a necessary lens for understanding the histories of both American higher education and civic life. Like many institutions of higher education, HBCUs have undergone significant transformations over the last 150 years. Schools like Morehouse, Spelman College, and Howard University continue to set the standard for schools that educate future political leaders and scholars committed to public service. Around 40% of Black politicians in the United States attended an HBCU. While most HBCUs have a majority Black student body, non-Black students are enrolling with greater frequency. As these institutions evolve over time, their histories remain vital for understanding the transformation of the United States.

Below, we feature an interview with Deondra Rose, Kevin D. Gorter Associate Professor of Public Policy at Duke University. Her recently published book, The Power of Black Excellence: HBCUs and the Fight for American Democracy offers a history of the impact of HBCUs on American political development and democracy.

Scholarly Sources

Q: What are you reading right now?

A: I am reading a few books. The one I’m most excited about right now is The Love Songs of W.E.B. DuBois by Honoree Fanonne Jeffers.

Q: What is your favorite book or essay to assign to give to people and why?

A: I love assigning and sharing Timothy Tyson’s “The Ghosts of 1898,” which offers a stunning account of the race riot in Wilmington, NC that marked a critical turning point in the nation’s political history. During the post-Civil War Reconstruction period, Wilmington had become a thriving hub of multiracial engagement in economic, social, civic, and political life. A violent massacre and municipal coup d’etat mounted by White supremacists who objected to Black citizens’ full inclusion among the city’s leadership and citizenship marked a decisive turn toward—and steadfast commitment to—Jim Crow racism throughout the South. I did not learn about the Wilmington massacre until well after my college years, when I read this piece as a faculty member at Duke. I was stunned that such a crucial event was not a hallmark of my early education in U.S. history. Analyzing this case provides powerful insight into how our understanding (and, often, lack of full understanding) of history shapes our perspectives on contemporary challenges facing various groups in the United States. It also raises important questions about responsibility for addressing past wrongs.

Q: Is there a book you read as a student that had a particularly profound impact on your trajectory as a scholar?

A: Suzanne Mettler’s Soldiers to Citizens: The G.I. Bill and the Making of the Greatest Generation and Theda Skocpol’s Protecting Soldiers and Mothers: The Political Origins of Social Policy in the United States ignited my interest in American political development and offer masterful examples of truly outstanding scholarship that I have always viewed as the gold standard.

Q: Which deceased writer would you most like to meet and why?

A: I would love to have met suspense writer Mary Higgins Clark. Beginning in eighth grade, I read every book that she has written—a body of work that includes roughly one book published every year since the 1970s. From about 1998 until she sadly passed away in 2020, I eagerly awaited the publication of each new book. If I had the chance to meet her, I would love to learn more about her approach to writing fiction and the disciplined writing process that drove her extraordinary productivity over the years.

Q: What's the best book you've read in the past year?

A: I read James Baldwin’s Go, Tell It On the Mountain and thoroughly enjoyed it.

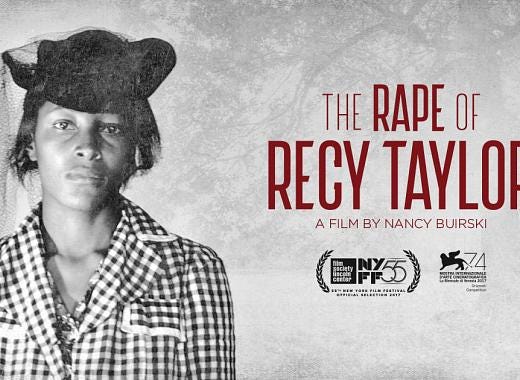

Q: Have you seen any documentaries that left an impression on you recently?

A: I love documentaries, and the one that I can’t stop thinking about is The Rape of Recy Taylor. This film offers a powerful account of the danger and injustice that many Black women faced in the Jim Crow South. It delves into the particular courage that it took to speak out against sexual violence in a society that demanded silence and looking the other way when certain citizens—particularly Black women—were harmed.

Q: What do you plan on reading next?

A: The next book in my queue is Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, which I’m especially excited to read as I embark on new writing projects during a sabbatical semester. As I begin new work, I love to find inspiration in how other writers approach their art.

Q: Who should read The Power of Black Excellence: HBCUs and the Fight for American Democracy and why?

A: I hope that anyone who is interested in Black history, the history of U.S. higher education, and/or democratic citizenship will find The Power of Black Excellence useful for gaining new insight into how all three of these topics are connected. In addition to offering a history of the ways in which HBCUs and government have interacted since the inception of Black colleges in the nineteenth century, the book also offers insight from in-depth interviews with HBCU alumni and Black elected officials.

Listen to Deondra’s NBN interview here:

Pope Francis’ Favorite Book of 2024

A recommendation from Editor Caleb Zakarin

When I first learned about the new, 6-volume Brill Encyclopedia of Early Christianity, I struggled to wrap my mind around how someone, even a group of scholars, could go about producing such a tome. In my conversation with Professor David G. Hunter, I learned that there is no great mystery. It takes years (in this case around 15) and hundreds of contributors. For David and his co-editors, this encyclopedia was clearly a labor of love and a contribution meant to lighten the load of scholars working on everything from late antiquity and Middle Eastern studies to theology and Patristics. If you’ve ever seen a massive encyclopedia set and wondered how it came to be, listen to my interview with David.

Perhaps the most astonishing thing about this encyclopedia is that David and his co-editors got to personally hand deliver a copy to Pope Francis in Vatican City. While Pope Francis did not formally cite the encyclopedia as his favorite book of the year, I can’t imagine there’s any other book he would pick.

Your Presence is Mandatory: How Fiction Deepens History

An essay by Leo Bader

Following the death of author Sasha Vasilyuk’s grandfather, Yefim Shulman, a note was discovered in which he confessed to having kept secret his capture while a Soviet soldier in World War II. Your Presence is Mandatory is Vasilyuk’s novelistic expansion of this piece of family history into a sweeping story ranging from the start of World War II to the return of war to eastern Ukraine from 2014 onwards.

In the novel, Yefim is a Ukrainian Jew in the Red Army who is captured in the early stages of the war. Capture, for the Soviets, is akin to treason— so Yefim hides the truth from his family and the world, until he is forced to reveal it to the KGB. His confession is only discovered by his family after his death. While Vasilyuk writes a deeply personal story, the scope of her novel forces reflection on broader themes of Ukrainian society and politics— the control of historical narrative in the Soviet Union, Ukrainian national identity and politics of memory, and, of course, the current Russo-Ukrainian war.

With any work of historical fiction, a stronger understanding of the dynamics surrounding the story means a greater enjoyment of the story itself. Central to Vasilyuk’s novel is the careful, state-sponsored construction of history in the Soviet Union, and the narrative divergence that occurs in former Soviet republics after the USSR’s collapse. Yefim, with his Ukrainian Jewish identity, is not in the least spared. Vasilyuk points out that Jewish Soviet soldiers who survived the war— only about 5,000 of the 500,000 that served— were regarded with suspicion, if not outright hostility, in the postwar period. Olga Bertelsen’s work In the Labyrinth of the KGB: Ukraine’s Intelligentsia in the 1960s-1970s documents the antisemitism of both Stalin and Khruschev, under whose direction the KGB worked to quash Ukrainian Zionist movements after World War II. These efforts which included assassinations, isolating dissidents in psychiatric facilities, and turning “everything that moved” into an informant, were part of a broader push to promote a Soviet identity that erased regional and ethnic particularities expressed through literature and art. The effort to subdue nationalist sentiments was an extension of the war itself, writes Mark Edele in Stalinism at War: The Soviet Union in World War II. Even after armed nationalist resistances had been subdued, Soviet forces continued to pursue activists and dissidents in the years following the war. Meanwhile, the “Great Patriotic War,” as World War II was remembered, was recounted as a story of national defense and liberation. Edele points out that in Russia today this narrative has become central to an emerging “cult of the war” that helps to inform policy decisions.

In Vasilyuk’s story, Yefim starts out as a young soldier enthusiastic about the Soviet project, unaware of the state’s hand in the famine that rocked Ukraine in the 1930s. However, he and his wife Nina gradually become disillusioned with the Soviet state over the course of the postwar period, illustrating the fallibility of the official history. When the Soviet Union collapses in 1991, national narratives begin to form and diverge, as Tatiana Zhurzhenko describes in War and Memory in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. Vasilyuk’s own grandparents discovered the state’s role in the famine only after the collapse. Histories of World War II have become “political technologies,” that were used, for example, on both sides of the Maidan protests in 2014 in Ukraine. Russia, meanwhile, has positioned itself as a great power successor to the USSR in its glorification of the war.

In the novel, when Nina returns to the eastern Ukrainian city of Donetsk in 2015, the endpoint of this political instrumentalization is visible: once again, the city is wracked by conflict, and Ukraine is once more threatened by imperial ambition. The historical parallels are made clear in the title of Serhii Plokhy’s analysis of what has led to the current conflict, The Russo-Ukrainian War: The Return of History. Plokhy argues that Vladimir Putin’s ambitions are an extension of the imperialist ideology that emerged in 19th century Russia, and that the history of World War II is central to Putin’s justification of his invasion in claiming that the Ukrainian government is rife with Nazis. This wholly inaccurate assertion seeks to make central the collaboration between Ukrainian nationalists and German forces during World War II.

Vasilyuk finished the book not long after the full-scale war in Ukraine started and describes her writing having acquired a mission that it did not fully have before. “State-sanctioned history is not always correct,” she says. Hearing the stories of those who were present in these histories, like Yefim’s or Vasilyuk’s family—exploring what Zhurzhenko, in War and Memory, calls “communities of memory”—undermines the ability of official histories to propagandize, whether in World War II, the Cold War, or today.

NBN has interviewed the authors of all books mentioned in this essay. Give them a listen, and share them with a friend!