Drugs in America

Featuring a conversation with Professor Matthew Lassiter about The Suburban Crisis.

Policing and Drugs

On the New Books Network, we try to feature scholarly conversations on even the most difficult of topics, such as policing and drugs. On New Books in Policing, Incarceration, and Reform, we host authors who study how policing operates globally and historically, in addition to those who study how to make carceral systems more humane. On New Books in Drugs, Addiction, and Recovery, hosts speak with scholars on the scientific and sociological study of drugs, in addition to methods of recovery and research on addiction treatment.

Professor Matthew Lassiter has recently published The Suburban Crisis with Princeton University Press, a deep and penetrating history of how policing and public health institutions in America sought to control and punish drug users. The study of policing and drugs is a worthy entry point into understanding the politics and culture of a place. The Suburban Crisis shows how major national policy changes can bubble up from grassroots activists seeking to “protect” their children and community. Listen to our interview with Matt below:

Scholarly Sources

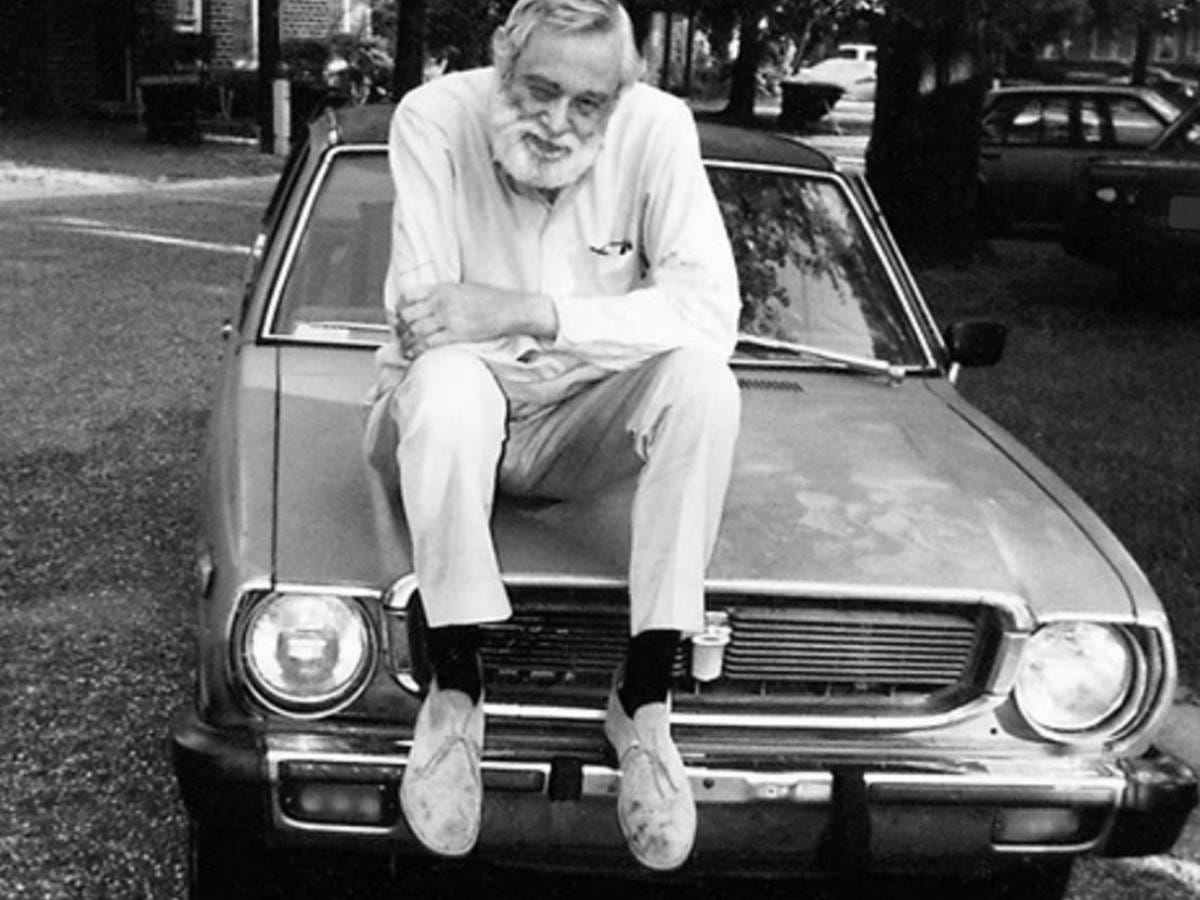

Matthew Lassiter is Professor of History, Professor of Urban and Regional Planning, and Arthur F. Thurnau Professor at the University of Michigan.

Q: You just published The Suburban Crisis with Princeton University Press. What was the most surprising thing you learned in studying the political history of the United States’ “war on drugs”?

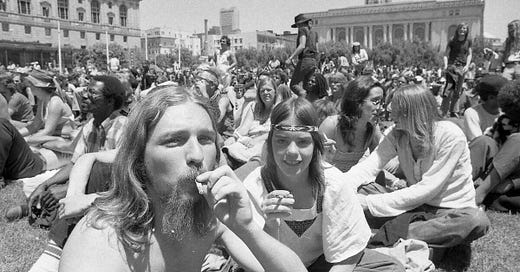

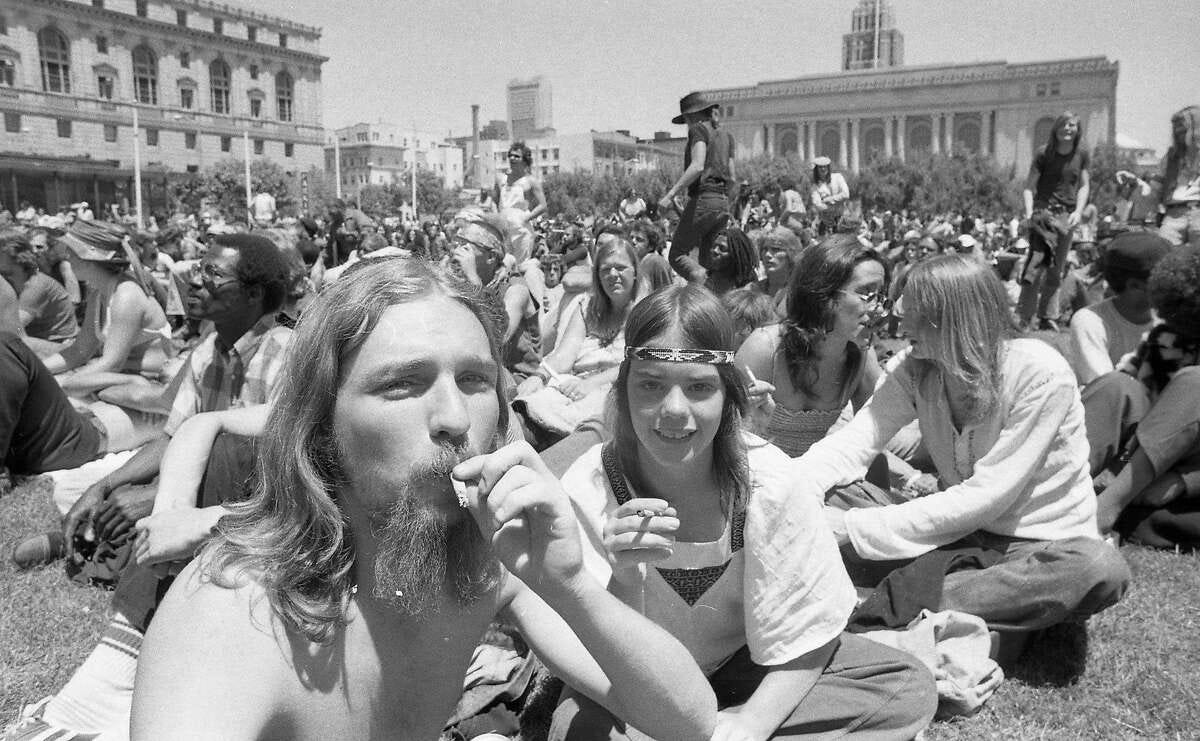

A: Until I dug into the archives, I did not realize that law enforcement had arrested millions of white middle-class teenagers and young adults for drug offenses, mostly involving marijuana possession, in the late 1960s and 1970s. The proportion of white drug arrests peaked in the mid-1970s at 81 percent of the total and 89 percent of juvenile drug arrests nationwide. The book excavates the diversionary and discretionary processes that policymakers and the criminal legal system designed to direct most of these white youth into rehabilitation programs rather than incarceration, the punishment disproportionately imposed on nonwhite and lower-income Americans.

Q: What are you reading right now?

A: I’m halfway through Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia, Launched Alternative Music and Changed American Culture by Grace Elizabeth Hale. It’s really great. I’m going to Athens in February for a three-night home stand by the Drive-By Truckers, so I figured that I should read about the town’s musical history—but it’s also helping me better understand the roots of the alternative subculture of my teenage years in suburban Atlanta during the 1980s.

Q: What is your favorite book or essay to assign to give to people and why?

A: Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. I always assign Trouillot at the start of the required methods and theory course for undergraduate history majors at the University of Michigan. The key insights of this 1995 masterpiece remain relevant and powerful: the most influential historical narratives are produced outside of academia; there is no clear line between primary and secondary sources, since all source creators are narrators with agendas; and silences in the archive are often deliberately produced by these historical actors.

Q: Is there a book you read as a student that had a particularly profound impact on your trajectory as a scholar?

A: Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland by Christopher Browning, originally published in 1992. I read Ordinary Men during my first year of graduate school, and it has powerfully influenced my thinking about the methods of social history and the ethics of writing with empathy while allocating historical responsibility broadly. Browning’s arguments about how social and cultural forces can make ordinary people do terrible things helped inform my agenda to explore grassroots politics in segregated white suburbs, rather than blaming historical outcomes mainly on political elites and top-down processes.

Q: Which deceased writer would you most like to meet and why?

A: Probably Richard Yates, the author of Revolutionary Road, my favorite book in the generally overwrought genre of affluent white suburban repression, dysfunction, and crisis. It’s an extraordinary debut novel, equal parts social criticism and suburban ethnography, clearly autobiographical in part. It’s also complicit in the midcentury cultural transformation of white suburbanites living in segregated suburbs into the alleged victims of their own landscapes of psychological conformity and pathology, what my book conceptualizes as the perpetual “suburban crisis.”

Q: What's the best book you've read in the past year?

A: Cormac McCarthy’s The Passenger. It’s not on the same extraordinary level as Blood Meridian or Suttree, but McCarthy is my favorite American author and it’s the better of his two-volume last hurrah.

7) Have you seen any films, documentaries, or museum exhibitions that left an impression on you recently?

I spent an afternoon at the Andy Warhol Museum, which is really impressive and deserves a much longer visit, during the recent Urban History Association meeting in Pittsburgh. I also just rewatched Serpico (1973), the brilliant Al Pacino movie about the high costs of exposing police corruption in New York City.

8) What do you plan on reading next?

I’ve been saving Stuart Schrader’s book Badges Without Borders: How Global Counterinsurgency Transformed American Policing, and am going to read it this semester while on sabbatical and finishing up a major website trilogy about the history of policing in Detroit. And several dissertations by University of Michigan students, as usual this time of year.