Does Democracy Need Distance?

Featuring an interview with philosopher Robert B. Talisse, a new series from Odd Lots, and a round-up of excellent Substacks.

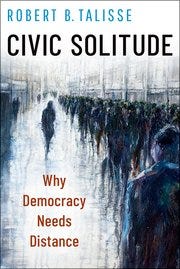

Civic Solitude

Philosopher Robert B. Talisse hosts New Books in Philosophy and has published a new book on democratic theory and practice with Oxford University Press titled Civic Solitude: Why Democracy Needs Distance. Read and listen to our thought-provoking interview with him below:

Q: Who should read Civic Solitude: Why Democracy Needs Distance and why?

A: Civic Solitude is the third in a trilogy of books about the responsibilities of democratic citizenship. Like its predecessors, it is written for my fellow citizens so I aspired to write in a way that’s accessible and engaging. More than that, the book focuses on what I expect are common experiences of politically attuned citizens: the sense that our democracy is endangered, that some of the perils we face come from inside our society, and that we need to find ways to reassure one another of our common investment in democratic politics. What I think is unique about Civic Solitude is that it begins with the observation that although we typically associate democracy with the citizens’ collective public action (democracy happens “in the streets,” we’re often told), there’s another important dimension to responsible citizenship, namely reflection. Yes, democracy needs active and publicly engaged citizens, but it also needs us to be able occasionally to stand apart from both our allies and foes and do some political thinking.

As I argue in the book, familiar modes of collective public democratic action can erode the cognitive and affective capacities we need in order to engage in the required modes of political reflection. Democracy indeed happens “in the streets,” but so does a lot else that’s not particularly democratic; moreover, democracy can also happen in quiet, non-commercial spaces where citizens can be alone with their thoughts: public libraries, public parks, and public museums. So, anyone who has the sense that perhaps our democracy has gotten too noisy, too in-your-face, and too frenetic for its own good should read Civic Solitude.

Q: You've been a host for New Books in Philosophy for over a decade. Can you recommend a few interviews that pair with your latest book?

A: Yes, I’ve been doing New Books in Philosophy since – what? – 2011? At one episode a month, that’s a lot of books. The interviews that immediately come to mind are more recent, though there are a few highlights from further in the past. Here goes:

My interview with Kevin Elliott about his book Democracy For Busy People is a natural touchstone. Elliott is concerned about the ways in which contemporary strategies for empowering ordinary democratic citizens are not only insufficiently attuned to the temporal constraints under which most citizens live, but they also tend to simply create new pathways for those who are already powerful to wield their influence. Elliott proposes his own conception of responsible citizenship which differs from what I propose in Civic Solitude, but our views are driven by many of the same concerns.

My interview with Alexandre Lefebvre about his Liberalism as a Way of Life was a lot of fun. The connection here is harder to get a hold of. The first thing to note is that the term liberalism here is used in the sense common among political philosophers, which is different from how the term is used in political discourse in the US. Liberalism in Alexandre’s book refers to a framework for thinking about politics that prioritizes individual liberty and autonomy, acknowledges tight limitations on what the State (or democratic majorities) can impose on people, and fosters a civic society in which individuals, within broad constraints, can live their own lives according to their own best judgments about what’s worthwhile. Alexandre argues that this philosophical framework is more than a theory of politics – it pervades our lives. Alexandre thinks that’s a good thing, because he thinks that the liberal way of life is in fact a model of human flourishing. The trilogy of which Civic Solitude is the completion is focused on the ways in which democracy can come undone precisely because we allow it to pervade our lives. I’m not sure there’s a tension between our views, but there is something to be worked out!

Wendy Salkin’s Speaking for Others: The Ethics of Informal Political Representation is another fantastic recent book whose connection to Civic Solitude is of interest to me. Wendy is the first to chart the normative issues pertaining to non-formal political representation – cases where, say, a US celebrity or rock star speaks to the broader public on behalf of a disadvantaged, marginalized, and often socially non-legible community. As you can intuitively discern, there are all kinds of ways this can go badly, but also ways in which non-formal representatives can do a lot of good. The connection to Civic Solitude has to do with the ways Wendy understands political identity, and how it can complicate our lives together, even when we’re committed to doing the right thing by one another.

Melvin Rogers’ The Darkened Light of Faith: Race, Democracy, and Freedom in African American Political Thought was another formative book and interview. Melvin works through a trajectory of social and political thought that stems from the struggle for abolition and works through the philosophical and artistic expressions of longing for liberty of the civil rights movement and beyond to uncover new ways of thinking about how one might sustain faith in democracy amidst ongoing, systematic, and horrendous injustice. Part of Civic Solitude argues that democratic citizens need to explore democratic idioms that lie beyond the political vernacular of contemporary struggles. I’m not sure whether Melvin would embrace this, but I see his book as an invitation to enter into the kind of civic reflection that Civic Solitude promotes.

David Estlund’s Utopophobia: On the Limits (If Any) of Political Philosophy is positioned in a similar space. David’s book is aptly described as rigorous philosophy; Utopophobia is a demanding book. But it is highly rewarding. David argues that, perhaps surprisingly, when thinking about the demands of justice it is an error to confine our ideas to what’s plausible or practicable. It may be, he argues, that justice makes demands on us that we cannot fulfill. The element of David’s book that connects with Civic Solitude is his insistence (which I am convinced is correctly placed) that we undercut our thinking about justice when we restrict ourselves to existing constraints. Like Melvin Rogers, David argues that thinking about justice must include exploration of normative ideas that lie beyond our current categories.

Finally, let me reach back to an interview I conducted a decade ago. Seana Shiffrin’s Speech Matters: On Lying, Morality, and the Laws presents her “thinker theory” of free speech. According to Seana’s view, the value of a functioning free speech system lies in the fact that we need to be able to access other’s free expression in order to fully understand our own ideas. A civic society of free speech is necessary for individual free thought. When I first encountered her work, I was almost instantly convinced – it articulated philosophically some vague intuitions I hadn’t been able to put together. In any case, Seana’s work helped me to start thinking more systematically about the need for a democracy to foster social conditions that enable self-criticism. In Civic Solitude, one of the main culprits I identify in diagnosing our present democratic dysfunctions is a political culture that incentivizes the snap-judgment, the “never blink” stance, and the idea that partisan loyalty is a value on to itself – all of these are tendencies that work against honest self-assessment. But we’re flawed creatures, and even when we believe what is true, we nonetheless can be cognitively improved. This insight is especially important in a democracy, so I argue.

Q: Philosophy books are often daunting for the uninitiated. How would you recommend someone take on personal study of philosophy?

A: Philosophy is a well-developed academic discipline, so one should expect that its major works will be daunting – nobody expects Chemistry books to be easy to read. However, Philosophy (perhaps unlike Chemistry) has the human condition as its subject matter – our struggles to know, understand, communicate, and live well. That suggests that Philosophy, even in its academic manifestations, should be accessible to anyone. I think the crucial thing to bring to one’s engagement with Philosophy is that it is a discipline committed to the possibility that just barely beneath a thin veneer of normalcy lies a vast sea of uncertainty, perplexity, vagueness, and confusion. The readiness to see the familiar as fundamentally strange, and to come to regard normalcy as illusory, is key to taking up any work in Philosophy. That’s not because one must accept the conclusions of those philosophers who defend counter-intuitive claims, but rather because the entire enterprise is fixated on that claims of that kind are not immediately dismissible. Learning to sit with difficult-to-imagine possibilities is what Philosophy is.

4) If you could have dinner with any dead philosopher, who would it be and what would you ask them?

Plato. My question would be: Why did you write Dialogues?

Check out more on the New Books in Philosophy channel here:

Follow Us on Bluesky

If you’re on Bluesky, give us a follow. You won’t regret it! (Click here)

An Eggcellent New Series

Odd Lots is an economics podcast that has garnered a cult-following over the years for its engaging and accessible analysis of the many complicated aspects of our modern financial system. With humor and curiosity, Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal facilitate conversations with leading academics and practitioners. Ever wondered how uranium is priced, how the Chinese economy actually functions, or why the Fed's impact is so difficult to predict? Tracy and Joe ask questions in a way that allows listeners with no prior knowledge or an already deep understanding of a given topic to learn something new.

Recently, they published an incredible new series called Beak Capitalism that examines the economy through the lens of the chicken industry. Give it a listen!

Substack Recommendations

Substack is quickly becoming the social media site where thoughtful ideas, dialogue, and writing can actually flourish. Many academics and authors are using it as a medium to promote their scholarly work in a casual format. On Substack, academics can connect with their most thoughtful readers and create an avenue to receive steady income outside the narrow confines of a university salary and book royalties. Below, we feature some of our favorite Substacks from scholars and authors. Comment any great ones that we missed!

Everything Is Broken

Music critic Seth Rogovoy meditates on culture, films, albums, and the messy aspects of political life. Highlights from this year include a discussion of Bob Dylan, a review of the Tony award-winning play Stereophonic, TV shows including Ted Lasso, and books such as The Oppermans.

Book Post

Excellent book reviews curated by Ann Kjellberg. Book Post features some of the best writers and artists on books you won’t find elsewhere.

The Academic Bubble

Historian Dion Georgiou offers book, film, and album recommendations alongside insightful analyses of popular culture. His “Rewound” column examines objects and episodes in political and cultural history, and in “One Take,” he gives a compelling take on the politics of a currently-running film.

Keen On

Andrew Keen’s recent episodes have covered an array of topics including artificial intelligence, the history of American sports stadiums, and how economic inequality has shaped the history of political thought.

The Intellectual Investor

Some highlights from Vitaliy Katsenelson’s most recent editions discuss the landscape of the electric vehicle industry, the telecom industry, and an introduction to classical music.

Lunch Box

In the latest editions of his newsletter, Frank Shyong reflects on a recent trip to Hong Kong, a feud between two food stands in Venice Beach, California, and identity through a search for Taiwanese breakfast.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it on social media or supporting us financially. Even just $1 a month makes a big difference.

Thanks for the shout out! x