Inside Italy

Italian Studies, Fashion History, and Library Science

In this week’s newsletter

Where in the World: Italy

Scholarly Sources with Elizabeth Currie

Meet a Host with Jen Hoyer

Where in the World: Italy

This week, check out a few great episodes with scholars who have examined empire, gender, and crime in Italy.

From Octavian’s victory at Actium (31 BC) to its traditional endpoint in the West (476 AD), the Roman Empire lasted a solid 500 years -- an impressive number by any standard, and fully one-fifth of all recorded history. In Rome: Strategy of Empire, James Lacey takes on an encompassing definition of strategy and focuses on crucial historical moments and the personalities involved to provide a persuasive and engaging history.

Women from the Ricasoli and Spinelli families formed a wide variety of social networks within and beyond Florence through their letters as they negotiated interpersonal relationships and lineage concerns to actively contribute to their families in early modern Italy. In Gender and Family Networks in Early Modern Italy, Meg Moran argues that a network model offers a framework of analysis in which to deconstruct patriarchy as a single system of institutionalized dominance in early modern Italy.

For over thirty years, modern Italy was plagued by ransom kidnappings perpetrated by bandits and organized crime syndicates. Nearly 700 men, women, and children were abducted from across the country between the late 1960s and the late 1990s. Ransom Kidnapping in Italy: Crime, Memory, and Violence by Alessandra Montalbano examines this Italian criminal phenomenon.

Subscribe to New Books in Italian Studies to learn more about the history, politics, and social life in Italy!

Scholarly Sources: Elizabeth Currie

Elizabeth Currie is a lecturer and author specializing in the history of textiles and dress. Currently teaching at Central Saint Martins and with previous roles at the Victoria and Albert Museum, she has published widely on fashion and design for general and specialist audiences.

Q: What are you reading right now?

A: I am reading the catalogue of an exhibition I visited this summer in Rome, Caravaggio 2025. I resisted buying it when I was in Italy, but I’m glad I changed my mind as it contains several interesting essays, for example on Caravaggio’s connections with different Roman workshops and the women who possibly modeled for him. It also includes some fantastic black and white photographs of the installation of the Caravaggio exhibition in Milan in 1951, which is often thought to mark the starting point for the artist’s new wave of popularity.

Q: What is your favorite book or essay to assign to give to people and why?

A: I often recommend Early Modern Things: Objects and their Histories, 1500-1800, edited by Paula Findlen, to students as an excellent example of both the material turn in early modern studies and concerted efforts over the last couple of decades to widen the geographical focus of scholarship. It examines the impact of the increasing circulation of artworks and objects, including books, and how this shaped people’s perceptions of themselves and the world around them.

It has been expanded in the second edition from 2021 with a section by authors whose work I admire on topics such as the role of Africa in international trade networks of luxury goods. Overall, the book features such a range of object types that really there is something for everyone.

Q: Is there a book you read as a student that had a particularly profound impact on your trajectory as a scholar?

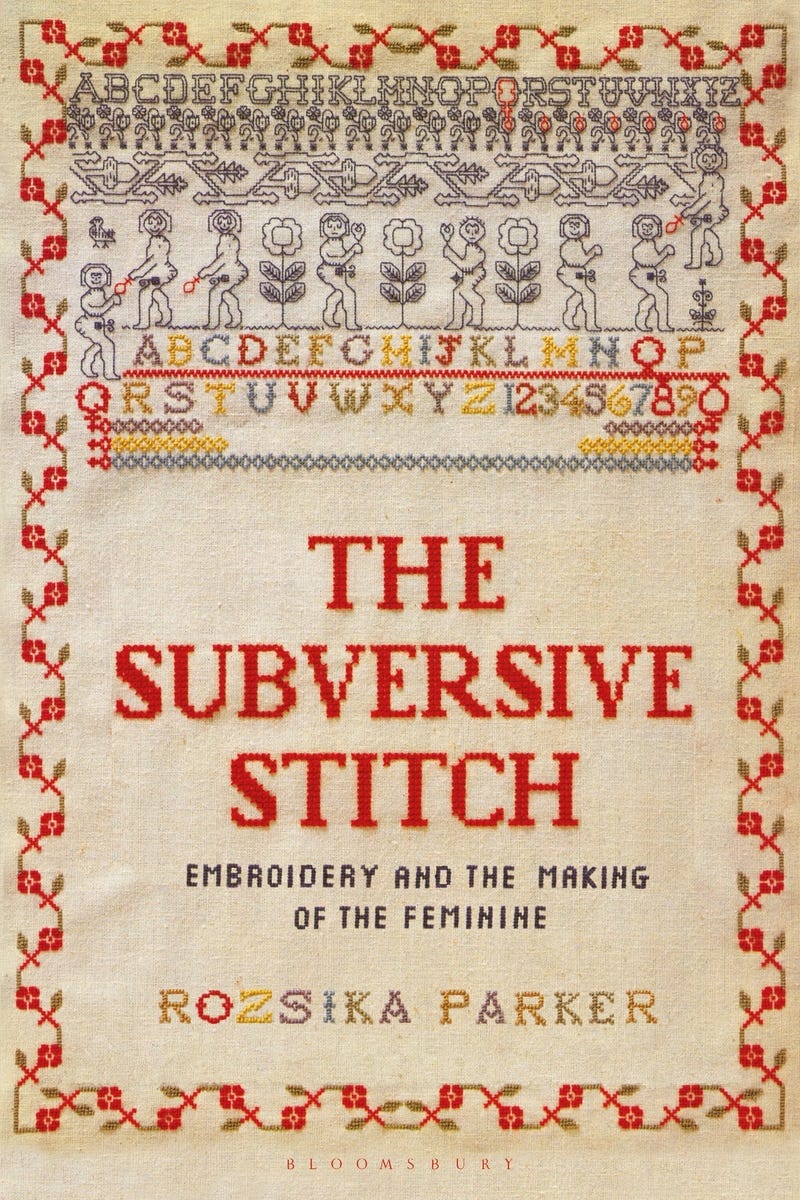

A: One of the first books I read that ignited my interest in textiles was Rozsika Parker’s The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. It explores the relationship between embroidery and gender ideals and the way needlework was associated with stereotypical female roles and attributes, as well as how individual women subverted this, turning stitching into a radical act. It takes in a whole range of related themes, such the changing boundaries between amateur and professional work, and focuses on some beautiful pieces to give a great insight into the variety of forms of early modern embroidery.

Inspired by The Subversive Stitch, I set off to Florence planning to write my dissertation on the production of embroidery in the city’s convents. I changed track when I realized how challenging it would be to locate sufficient primary sources, but Parker’s approach has influenced my thinking in many ways since then.

Q: Which deceased writer would you most like to meet and why?

A: Someone I would like to meet is the French author and philosopher Michel de Montaigne. He evidently enjoyed conversation with many different types of people: although he does not seem to have been thrilled to have encountered so many of his native countrymen in Rome. At one point he remarks that even beggars on the streets come up and speak to him in French. It would be fascinating to find out more about his impressions of Italy – I often consult his journal of the trip he undertook in 1580-1. The first part of the volume was dictated to a servant and it was published after Montaigne’s death. As might be expected, he doesn’t always focus on the obvious – he was apparently rather disappointed by Venice – so it gives an original perspective compared with other travel accounts from the same period.

Q: What’s the best book you’ve read in the past year?

A: One of the most thought-provoking books I’ve read this year is Kate Lowe’s Provenance and Possession: Acquisitions from the Portuguese Empire in Renaissance Italy about the collecting practices of Duke Cosimo de’ Medici and his family in Florence. She examines their motivations for procuring objects, animals, and also enslaved people from around the world. It is a masterclass in how to write histories when we are confronted with large gaps in the archive. Despite such challenges, Lowe has succeeded in tracking down some fascinating evidence to answer questions that have long perplexed researchers, such as how and when two impressive Kongolese oliphants - hunting horns made of carved elephant tusks - arrived in Florence.

Q: Have you seen any films, documentaries, or museum exhibitions that left an impression on you recently?

A: I’ve just been to Marseille and visited the Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilisations (MUCEM) for the first time. Perhaps not surprisingly for a new museum (it opened in 2013), the displays are very innovative and engaging. I particularly enjoyed the current temporary exhibition, Don Quixote, which has lots of books in it! It examines the influence of Miguel de Cervantes’ work from its initial publication to the present day, through a whole range of media including paintings, songs, and tapestries. It illustrates how different episodes in the book have been adopted for political, moral and philosophical purposes over centuries, but it is curated in an accessible and visually striking way. When we were there all the visitors, including some groups of school children, seemed very appreciative.

Q: What do you plan on reading next?

A: There are several books coming out in paperback early next year that I’m looking forward to reading, including Peter Davidson’s Relics, Dreams, Voyages: World Baroque. It focuses on some of the same social groups who appear in my book, such as mercenary soldiers, and I’m curious about the way different cultures absorb and reimagine particular types of material culture. I’m keen to find out more about the global connections it uncovers, such as a Japanese Christian statue and the development of a cult devoted to Mary Queen of Scots in Antwerp.

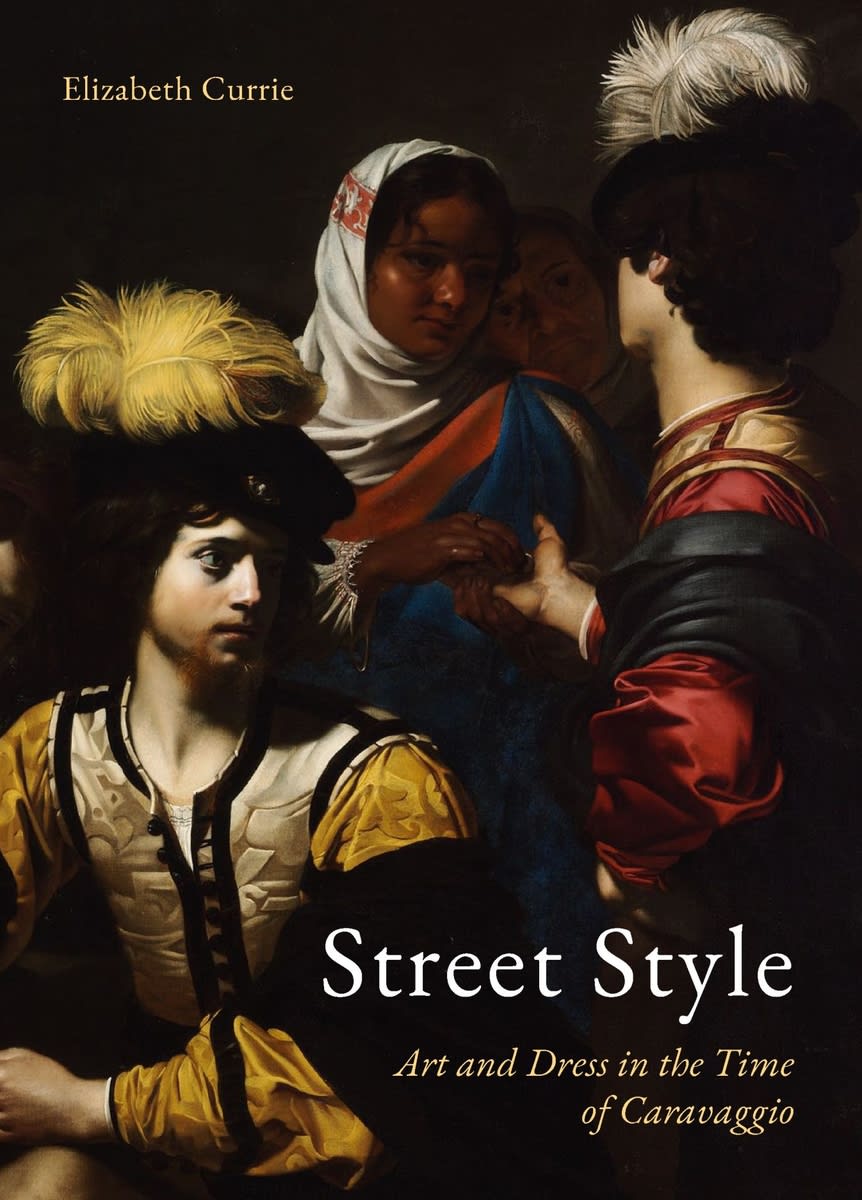

Q: Who should read your book Street Style: Art and Dress in the Time of Caravaggio and why?

A: I hope my book will interest anyone who wants to find out more about the art and social history of Italy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It examines why the poor became so visible in artworks at this time and thinks about the changing tastes of patrons and the art market. It shows how Caravaggio drew inspiration from the street life around him as well as other artistic and literary forms, such as popular theatre.

It is one of very few publications to focus on the clothing of the poor in early modern Italy, comparing and contrasting the dress we see on figures in artworks with what we know about the appearances of their real-life counterparts, based partly on written records, such as sumptuary laws, trials, and household inventories.

If you like to read about the experiences of people who are often overlooked in traditional histories, this is also a book for you, as each chapter focuses on a specific social group, from soldiers, sex workers and Romani fortune tellers to servants and pilgrims.

Q: Anything else you’d like to share, either about your academic work or creative endeavors?

A: I imagine this is an experience shared by many authors, but over the course of this year I’ve been surprised by the topical nature of Street Style, as it focuses partly on how minorities were treated and regulated in a growing city with a very mobile population. Some of the initiatives taken during the current Catholic jubilee in Rome, to ‘clean up’ the city in terms of its infrastructure and, to a smaller extent, in tackling problems of poverty, are also mirrored in the book. And the appeal of Caravaggio seems to go from strength to strength: he is the subject of at least two current displays at the Wallace Collection, London, and the Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg, Florida.

Check out Street Style: Art and Dress in the Time of Caravaggio and listen to Elizabeth’s great interview!

Subscribe to New Books in Art to learn from incredible scholars like Elizabeth, and learn about art, dress, design, other creative works!

Meet a Host: Jen Hoyer

Jen Hoyer is a librarian and archivist, living and working in New York City since 2013. She currently works as Technical Services and Electronic Resources Librarian at CUNY New York City College of Technology in Brooklyn, NY. More broadly, she works on a lot of different things connected to information access, pedagogy, and information production.

Q: Can you briefly introduce yourself including your areas of academic interest?

A: As a librarian, a lot of my work revolves around questions about who is producing information and who gets to access that information. While my day-to-day work deals with the technical aspects of that, I like asking broader questions about who has the authority to produce knowledge, who controls what information circulates, and how we can challenge norms about information access. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about information production as a tactic and a tool for change; a few projects connected with that this year include an article about a collective that took over the NYU printshop in May 1970 and a book I co-edited about OSPAAAL and their legacy for material production as solidarity work.

Q: How did you first hear about the New Books Network?

A: My friend Traci mentioned New Books Network several years ago; I think I had asked what her plans were after her latest degree (she has an impressive collection of those) and, to paraphrase her response, she explained that she was turning to NBN as a classroom. I started listening and was hooked.

Q: What made you want to be a host for NBN?

A: While I found NBN useful for engaging with new ideas and a broad range of scholarship, I was also frustrated that a lot of scholars in my own field of libraries and archives weren’t being interviewed. When I learned that it’s up to volunteer hosts to choose who is featured in episodes, I realized that it was up to me to help fix this problem. NBN is such a powerful tool that way; hosts can directly address representation disparities through the choices they make about who they interview. And, as a librarian who thinks a lot about providing access to information, I love that I can create new (free!) access points to books by interviewing authors about them.

Q: What channels do you contribute to?

A: My episodes initially appeared on the Scholarly Communication channel, and then the Library Science channel was created a few months later. I’ve contributed to a few other channels as well, usually when authors reach out to me about books I might be interested in that are a little outside my regular lane. I enjoy reading about more than libraries and archives, but with NBN I try to focus most of my energy on improving access to scholarship about information work broadly.

Q: What do you enjoy most about being an NBN host?

A: I feel like hosting on NBN is the best kept secret. I get to connect with so many really smart and interesting people, and they are usually pretty excited to spend time talking with me about their research. I’ve wrapped up so many interviews and thought to myself, “I can’t believe I’m lucky enough to have spent an hour with that person.”

Q: Other than your own, what has been your favorite episode (or channel) to listen to?

A: I’m too fickle to pick a favorite channel, but my favorite thing to do when I have time for a podcast is to look at what’s come out across NBN that day and pick the episode that jumps out at me. I’ve listened to so many interesting conversations that way! In terms of favorite episodes, I often think about Karen Levy’s interview on her book Data Driven.

Q: What advice would you give to anyone interested in becoming a host at NBN?

A: Hosting on New Books Network is an excellent way to actually read all (or most of...) the books on your To Be Read list!

Check out all of Jen’s great interviews on our Scholarly Communication and Library Science channels!

This roundup is such a rich entry point into understanding Italy beyond the usual political narratives. The Currie interview on Caravaggio and street fashion is fascinating becuase it shows how material culture and social hierarchies intersect in ways that reveal more about power dynamics than formal institutional analysis often does. Her point about the poor becoming visible in artwork precisely when cities were trying to "clean them up" during jubilees echos patterns we still see today,which makes the archive feel urgently relevant rather than just historical. These interviews do agreat job of showing how cultural and social history can illuminate political structures sideways.