A Second Cold War?

Featuring a new podcast, The Second Cold War Observatory, and an interview with historian Arash Azizi.

Second Cold War Observatory Podcast

The Second Cold War Observatory is a project of scholars studying our current age’s great power rivalries. In addition to organizing the publication of contemporary research in academic journals and presses, the Second Cold War Observatory also has a podcast that is now available on the New Books Network. Below, you can find an interview with hosts Dr. Seth Schindler and Dr. Jessica DiCarlo about the project, the podcast, and the importance of studying today’s conflicts through a cold war lens.

Q: What is the Second Cold War Observatory, and what is your mission?

A: We are a collective of scholars whose research focuses on contemporary great power rivalry. Currently comprising approximately 40 research associates based at universities across more than a dozen countries, the SCWO examines the remarkable intensification of great power competition that extends from the depths of the oceans to the Arctic regions and outer space.

While this competition is worldwide in scope, it plays out distinctly in different locations and contexts. Most of our members examine how contemporary great power rivalry manifests in particular places, such as the Atacama Desert, Mombasa, and Laos. Others investigate how geostrategic competition shapes particular sectors or networks, including semiconductor production networks, surveillance technology deployed in cities, and the transnational infrastructure networks transforming southern Africa. Our research combines global scope with local detail and analyzes traditional and emerging domains of rivalry.

Our shared mission is to provide deeper, more nuanced perspectives that transcend headlines that focus on diplomacy. Ultimately, we endeavor to document and analyze how contemporary great power competition shapes our world.

Q: Some people bristle at the term “second cold war,” why shouldn’t they?

A: It is worth remembering that the term “cold war” was popularized by George Orwell in the late 1940s. It stuck because it so aptly described the state of relations between the US and USSR. Similarly, we use the term “Second Cold War” to describe relations between the US and China and their respective allies. It’s no secret that geopolitical rivalry is a leitmotif of our era. Moreover, we hope to highlight historical continuity, and this speaks to a debate that unfolded a few years ago on whether “cold war” was an appropriate analogy for contemporary US-China relations. We find the term analytically useful because it situates current great power competition within a historical framework while acknowledging its distinct contemporary features. We think it’s unhelpful to interpret the contemporary challenge to US power in isolation from the Cold War. Rather than an entirely new era that resembles the Cold War, we argue that the challenge posed to the US-led international order represents a resumption of Cold War-era hostilities.

This began in earnest after the 2008 financial crisis, and while contemporary geopolitical rivalry differs in many ways from the Cold War, it makes sense to understand them as discrete events in a much longer historical process. In a way, it’s similar to how most people think of the World Wars. Each had its own dynamics, and they exhibited significant differences from one another, but they were events in a series. Similarly, the Second Cold War differs from its namesake in many ways.

First and foremost is its spatial logic. Rather than competing to incorporate countries into territorial blocs, the US and China are active in most countries where they compete for influence. It is inconceivable that either could contain the other in a geographic sense. Meanwhile, they are interdependent and will remain so for the foreseeable future, even if there is some decoupling in strategic sectors. So rather than compete for territory, and in the context of their continued interdependence, the US and China compete to control the networks that constitute the architecture of globalization. Competition is fiercest in infrastructure, digital, production, and finance networks.

We underscore that failing to acknowledge the historical roots of the current conjuncture risks normalizing the period of hyper-globalization that preceded it. That era was actually historically exceptional, and challenges to unrivaled US power were almost inevitable. Rather than bristle at the term, we should use it precisely to make sense of the present historical moment and the unique dynamics of contemporary great power competition.

Q: What books would you recommend people read that have come out in the last couple of years and why?

A: We read broadly, and one of our primary activities is a reading group. We have learned a lot from recent Cold War history. Odd Arne Westad’s The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times rejected the notion that the Cold War was an epic bipolar rivalry “for the soul of mankind.” Instead, he interpreted it as a global event. The US and USSR were powerful protagonists, but it was also shaped by a host of other actors. Scholarship on the “Global Cold War” proliferated in the wake of this book, and for these scholars, the Cold War is an era, period, or context. The US, USSR, and, for a period, China, competed globally, but they often struggled to determine outcomes.

Lorenz Lüthi’s book Cold Wars: Asia, The Middle East, Europe makes this point well. We especially enjoyed Sara Lorenzini’s book Global Development: A Cold War History on how the Cold War was the context for the establishment of the institutions, concepts, and discourses that structured and persist in development and foreign aid today. We’ve also enjoyed Jeremy Friedman’s books, which read like a two-volume series, Shadow Cold War: The Sino-Soviet Competition for the Third World, and the more recent Ripe for Revolution: Building Socialism in the Third World. Sergey Radchenko’s recently published account entitled To Run the World: The Kremlin’s Cold War Bid for Global Power is somewhat of a corrective because his focus is on the US-Soviet rivalry, but it’s interpreted as a global event— and importantly, he focuses on the USSR’s objectives.

Both Fritz Bartel’s The Triumph of Broken Promises: The End of the Cold War and the Rise of Neoliberalism, and Daniel Sargent’s Superpower Transformed: The Remaking of American Foreign Relations in the 1970s, offer prescient analyses of the transition period of the 1970s when Brezhnev and Nixon were invested in détente; meanwhile, the US and China established formal relations, allowing for the emergence of proto-globalization. Vladislav Zubok’s recent account of the USSR’s decline and collapse— Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union— is unparalleled.

Many books have been published recently on various aspects of the US-China rivalry. Adam Tooze’s Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World is in a class by itself when it comes to explaining how the market for securitized subprime mortgages collapsed. Everything changed after that. Within the SCWO, we tend to appreciate books that are aligned with the analytical approach of contemporary Cold War historians insofar as they are multi-sited and put localized events in a global perspective. Examples include Chip War: The Fight for the World's Most Critical Technology by Chris Miller, Volt Rush: The Winners and Losers in the Race to Go Green by Henry Sanderson, and Rivers of Iron: Railroads and Chinese Power in Southeast Asia by David Lampton, Selina Ho, and Cheng-Chwee Kuik.

Finally, many of our listeners may not be familiar with China. However, it’s impossible to understand the contemporary moment without a deep understanding of China. Unfortunately, there are many hyperbolic books about China that reproduce clichés. For readers with limited knowledge of China, Maurice Meisner’s remarkable Mao’s China and After: A History of the People's Republic is a great starting point. For those interested in political history, Alexander Pantsov and Steven Levine’s biographic epic Mao: The Real Story is unique because it draws on Soviet archives. We’ve enjoyed several books that focus more on domestic China, including Birth of the Geopolitical Age: Global Frontiers and the Making of Modern China by Shellen Wu, Seeking Truth and Hiding Facts: Information, Ideology, and Authoritarianism in China by Jeremy L. Wallace, and Ecological States: Politics of Science and Nature in Urbanizing China by Jesse Rodenbiker.

There has also been a boom in “Global China” research that provides a grounded understanding of China’s global integration around the world, challenging widely circulating preconceptions about the rise of China and China’s role in the world. C.K. Lee’s The Specter of Global China: Politics, Labor, and Foreign Investment in Africa is a book to start with in this field. In Rosewood: Endangered Species Conservation and the Rise of Global China (2022), Annah Lake Zhu offers a rigorous look at China’s growing environmentalism through the boom in rosewood trade between China and Madagascar and how it disrupts Western conservation models. Belt and Road: The First Decade by Igor Rogelja and Konstantinos Tsimonis offers a balanced look back on the first 10 years of the BRI. The recent volume Seeing China’s Belt and Road edited by Edward Schatz and Rachel Silvey, features grounded fieldwork that allows for different ways of seeing the changing world order and China’s role in it through understudied “downstream” contexts.

Finally, select books by our members include:

The Rise of the Infrastructure State: How US-China Rivalry Shapes Politics and Place Worldwide

In China’s Wake: How the Commodity Boom Transformed Development Strategies in the Global South

The Political Economy of China’s Infrastructure Development in Africa: Capital, State Agency, Debt

Fractured China: How State Transformation Is Shaping China’s Rise.

Q: What is the role of scholars in the midst of global conflict? What do you discuss on the podcast, and who should listen?

A: As academics, we feel a responsibility to challenge common-sense understandings and assumptions, and instead provide deep analysis beyond headline narratives. This means analyzing how global competition manifests, bridging theoretical understanding with practical implications, maintaining scholarly objectivity while engaging with pressing issues, and contributing to public understanding of complex geopolitical dynamics. We view the podcast as one medium to achieve these goals.

Each episode focuses on a particular aspect of rivalry, ranging from the incorporation of digital platforms like Alibaba and Google and micro-geopolitics in Nairobi, to Chinese ‘smart city’ surveillance technology in Latin America, to industrial policy and spatial planning along Europe’s eastern border, and financial geopolitics through sovereign debt and development finance. In these episodes, we try to cover the overarching context of great power rivalry and drill down into its particular manifestations.

By providing grounded analysis and perspectives and examining how rivalry shapes certain sectors and places, we avoid simplistic views of US-China competition. Others who want to better understand the impact of geopolitical rivalry beyond the headlines that sometimes treat the US-China rivalry as a sporting match will hopefully like a variety of episodes. Finally, what makes the podcast particularly valuable is its commitment to accessibility while maintaining depth, specificity, and scholarly rigor.

Scholarly Sources

Arash Azizi is a writer and historian. He is a visiting fellow at Boston University’s Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future and a contributing writer at The Atlantic.

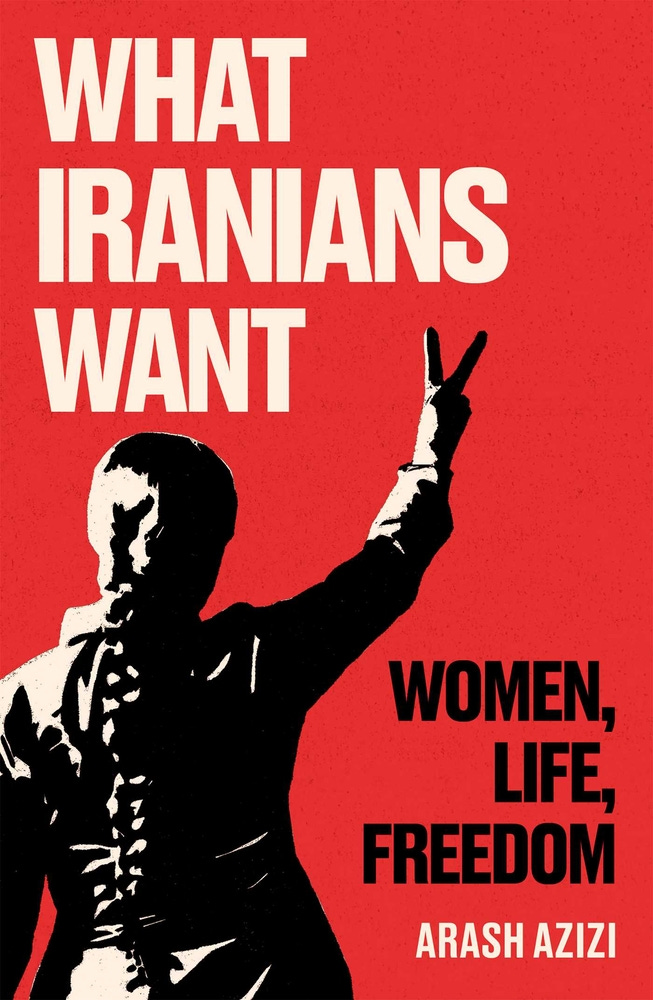

Arash is the author of What Iranians Want: Women, Life, Freedom, published earlier this year. Listen to his interview below:

Q: What are you reading right now?

A: The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates, On Settler-Colonialism: Ideology, Violence, and Justice by Adam Kirsch, and The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa.

Q: What is your favorite book or essay to assign or give to people and why?

A: Always tough to pick one. But I'll go with two: The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels because it's the most seminal text of the modern era and also shows the power of a historical account acting as a political manifesto. Also, Discourse on Colonialism by Aimé Césaire because it's such a great spotlight on one particular moment in world history.

Q: Is there a book you read as a student that had a particularly profound impact on your trajectory as a scholar?

A: I'll name two: Reappraisals: Reflections on the Forgotten Twentieth Century by Tony Judt. It was given to me by a friend, not a professor, and I devoured every page. Murder in Amsterdam: Liberal Europe, Islam and the Limits of Tolerance by Ian Buruma, assigned to me by Professor Anna Shternshis at University of Toronto, is another. I appreciated the content of these books, and they taught me what books could do with form.

Q: Which deceased writer would you most like to meet and why?

A: I am not that big on meeting my favorite writers. The main joy is reading them, not having a beer with them! But if I wanted to pick one, it'd have to be George Orwell. I wonder how he would be in political debates in person.

Q: What's the best book you've read in the past year?

A: Let me pick four? The Rebel's Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon by Adam Shatz, When the Clock Broke by John Ganz, If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution by Vincent Bevins and The last Alleyway by Daryoush Karimi which I read in Persian.

Q: Have you seen any films that left an impression on you recently?

A: I loved the film, The Old Oak by Ken Loach. It shook me hard. I loved how it didn't sugar coat things and how deeply bitter and tragic it was; reflecting the state of the left and socialist movements that it depicts. This makes it very sad for me, of course. Especially since Loach is now 87 and this is likely his last film or one of his last films. It's almost like he admitted defeat with this film.

Q: What do you plan on reading next?

A: In the Name of Identity: Violence and the Need to Belong by Amin Maalouf.

Q: Who should read your book, What Iranians Want: Women, Life, Freedom and why?

A: It's a book about a bunch of people I find endlessly fascinating. Anybody who wants to hear stories of people, mostly women, who keep rising up for freedom against all odds.